During World War II

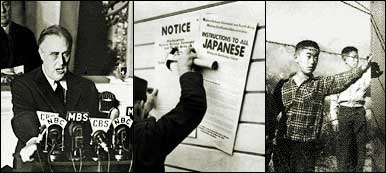

From the US Army’s Western Defense Command, a few hundred yards from the MIS classroom and pursuant to President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, General John L. Dewitt issued the fateful series of orders leading to the mass removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Thus, even as their training intensified, MIS soldiers learned that their families had lost their jobs, homes, farms, and businesses and were being imprisoned in detention centers in the interior of the country.

Although only one class would graduate from the Building 640 facility, the valuable mission it began at the Presidio would continue at Camp Savage and Fort Snelling in Minnesota, where, in the wake of the mass evacuation of Nisei from the West Coast, the MIS Language School was forced to relocate.

The impact of the MIS

From these humble beginnings, the MIS Language School would eventually train more than six thousand Japanese language specialists for service throughout the world. The MIS had its most significant impact in the Pacific theater, where Japanese American linguists participated in every major battle and campaign against Japan. Soldiers of the MIS served as undercover agents in the Philippines, fought behind enemy lines with Merrill’s Marauders in Burma, endured jungle warfare in New Guinea, landed with the Marines on the beaches Iwo Jima, and crawled into the caves of Saipan to persuade suicidal enemy forces to surrender.

Unlike other combatants in the war, the men of the MIS faced danger on every side — from the enemy Japanese troops to their fellow American and Allied soldiers, who viewed them with suspicion and too easily mistook them for the enemy. The MIS gave the Allies a significant advantage during the war. In the field, MIS personnel gleaned vital operational knowledge through the skillful interrogation of prisoners and the translation of captured diaries, maps, and other documents. They performed other tasks as well, volunteering for reconnaissance patrols and similar combat duties. On at least one occasion, an MIS soldier helped win an engagement by creeping up to enemy lines and impersonating a Japanese officer’s commands to his troops.

At headquarters level, the MIS handled raw intelligence obtained from the field and communications intercepts, intelligence that provided the Allies with a clear strategic advantage. Among their accomplishments: translating the Japanese Navy’s “Z Plan” for Pacific conquest, documenting the Japanese military’s order of battle, and supporting the code breaking efforts that led to the downing of Admiral Yamamoto’s plane.