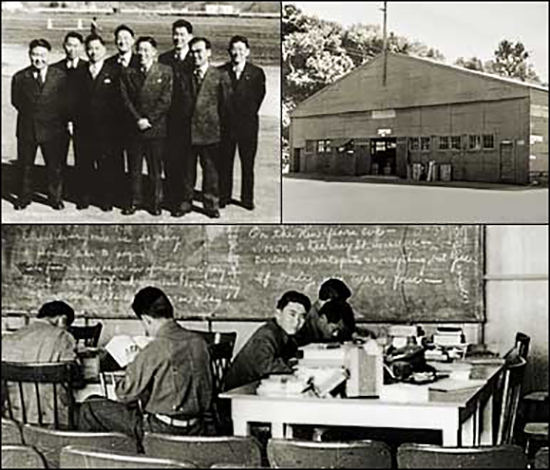

In the foreground of the Golden Gate Bridge, the Presidio of San Francisco’s Building 640 stands as a symbol of patriotism and civil liberties. Here in the structure once used as an air mail carrier depot and a gymnasium at the Presidio of San Francisco, were secretly trained and housed the first class of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) Language School, the forerunner of the renowned Defense Language Institute at the Presidio of Monterey.

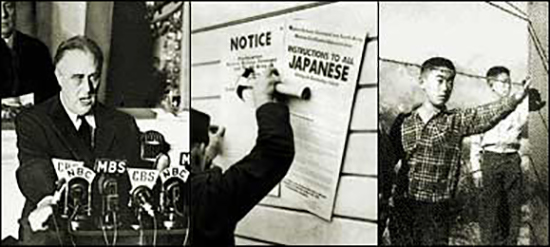

Like many pivotal experiences in history, the MIS story is replete with ironies. Just one month prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, on November 1, 1941, the first group of recruits of 58 Japanese American (Nisei) and two Caucasians began their secret language studies with their four Nisei instructors in makeshift classrooms and barracks of Building 640 at Crissy Field in the Presidio of San Francisco. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, everything changed. The first class soldiers hastened their studies to only six months, culminating in their deployment to the Pacific theatre of war by May 1942. Ironically, pursuant to Executive Order 9066, their families were among 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry who would be forcibly removed from their homes and incarcerated in remote confinement camps throughout the US. The school had to relocate to Camp Savage and later Fort Snelling, MN as the Military Intelligence Service Language School. It trained over 6,000 linguist soldiers, many of them Nisei by war’s end. Attached to every combat unit in the Pacific War, these MIS soldier linguists translated documents, intercepted intelligence, impersonated the enemy in battle, gathered key intelligence from prisoners-of-war, and volunteered for dangerous missions.

Their intimate knowledge of the language and culture helped gain a tactical and strategic advantage over their opponents. The MIS is credited for saving countless lives, shortening the war by 2 years and ultimately winning the war. In the aftermath, many MIS effected the peaceful transition in the Occupation of Japan. As “grassroots” ambassadors, they helped lay the groundwork for Japan’s democracy.

The MIS Language school relocated to the Presidio of Monterey which has become the pre-eminent military intelligence language training center for the US Armed Forces. Six decades later the MIS were honored with a Presidential Unit Citation in 2000 and the Nisei soldiers of the MIS were among those awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2011.

Before Pearl Harbor

In anticipation of war against Japan, the US began assessing and recruiting already enlisted soldiers of Japanese descent proficient in the Japanese Language in June 1942. From the US Army’s Western Defense Command, a few hundred yards from the Golden Gate Bridge, the US Army Language School was established on November 1, 1941 under General John L. DeWitt in an old 1920 abandoned airplane hangar, what was once used to house airmail airplanes. This top-secret school trained the first class of 60 students, 58 Japanese Americans (Nisei) and two Caucasians with four instructors. John Aiso, a graduate of Harvard Law School, recently drafted, would be designated the school’s headmaster.

During World War II

Although only one class would graduate from the Building 640 facility in May 1942, the valuable mission it began at the Presidio would continue at Camp Savage and Fort Snelling in Minnesota, where, in the wake of the mass eviction of Nisei from the West Coast, the MIS Language School was forced to relocate. Pursuant to Executive Order 9066 issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, General Dewitt would issue a series of military proclamations which would lead to the eventual round up and forced removal and incarceration of some 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast.

The Impact of the MIS

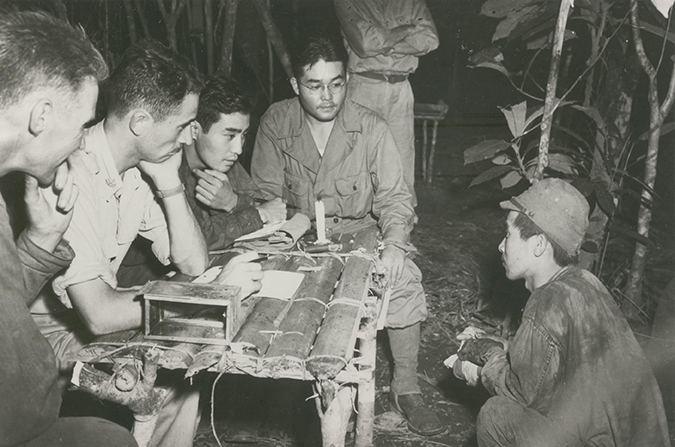

From these humble beginnings, the MIS Language School would eventually train more than six thousand Japanese language specialists for service throughout the world. The MIS had its most significant impact in the Pacific theater, where Japanese American linguists participated in every major battle and campaign against Japan. Soldiers of the MIS served as translators of captured documents, linguists behind enemy lines with Merrill’s Marauders in Burma, endured jungle warfare in New Guinea, landed with the Marines on the beaches of Iwo Jima, and crawled into the caves of Saipan and Okinawa to persuade suicidal enemy forces to surrender.

Unlike other combatants in the war, the men of the MIS faced danger on every side — from the enemy Japanese troops, to their fellow American and Allied soldiers, who viewed them with suspicion and too easily mistook them for the enemy. The MIS gave the Allies a significant advantage during the war. In the field, MIS personnel gleaned vital operational knowledge through the skillful interrogation of prisoners and the translation of captured diaries, maps, and other documents. They performed other tasks as well, volunteering for reconnaissance patrols and similar combat duties. On at least one occasion, an MIS soldier helped win an engagement by creeping up to enemy lines and impersonating a Japanese officer’s commands to his troops.

At headquarters level, the MIS handled raw intelligence obtained from the field and communications intercepts, intelligence that provided the Allies with a clear strategic advantage. Among their accomplishments: translating the Japanese Navy’s “Z Plan” for Pacific conquest, documenting the Japanese military’s order of battle, and supporting the code breaking efforts that led to the downing of Admiral Yamamoto’s plane.

The MIS Contribution After the War

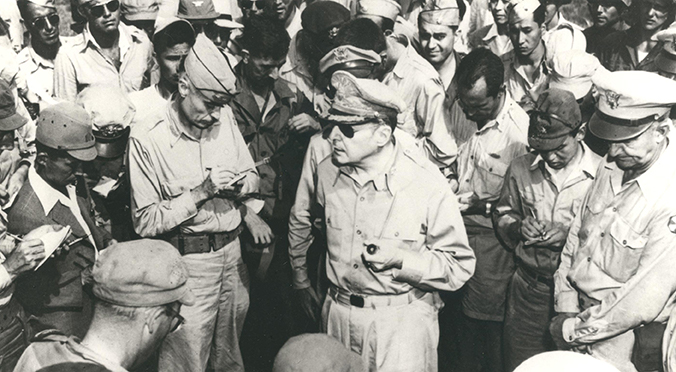

After the war, MIS soldiers played a critical role in the Occupation of Japan serving as a vital link between General Douglas Macarthur and the Japanese people. With their knowledge of Japanese language and culture, the Nisei of the MIS helped to secure the peace and establish Japan’s democratic institutions. They assisted in every aspect of Japan’s reconstruction, from land reform and education to civil and legal affairs.

The MIS contributed to Japan’s transition from a country ravaged by war to a great economic power and one of America’s most important allies. Just as the Golden Gate Bridge symbolizes the historical linkage between East and West, the MIS “goodwill ambassadors” represented a vital liaison between the United States and Japan in the critical postwar years.

The MIS also paved the way for integrating language in military planning and operations, a role consistent with the postwar policy of international engagement. Today, foreign language skills are integral to military intelligence collection and analysis. In fact, the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Service, the military’s premier language training school, located at the Presidio of Monterey, California, traces its origins directly to the modest classroom located in Building 640 on the grounds of the Presidio.

The MIS Story — its contribution to the war effort, to the rebuilding of Japan, to the development of national security capabilities, and its significance to the larger American story — went largely unrecognized. Due to service’s highly classified mission, the very existence of the MIS only became known to the general public with the passage of the Freedom of Information Act of 1971.

Recognition

In recent years, thanks to Congressional advocacy, MIS veterans have been accorded a measure of recognition by the US Government. Scores of MIS veterans have belatedly received medal upgrades, from the Bronze Star to the Distinguished Service Medal. In 2000, the Presidential Unit Citation, the military’s highest unit decoration, was retroactively awarded to all members of the MIS who served in WWII, in recognition of their collective contribution to the war effort. The US Army has commissioned a comprehensive history (Nisei Linguists, James MacNaughton) of the MIS that sheds further light on the scope and value of the MIS’s work. Through congressional legislation, the veterans of the Military Intelligence Service received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2011, our nation’s highest honor for their distinguished service during World War II.

These promising but disparate efforts to honor and explain the significance of the MIS would find their highest expression in the Military Intelligence Service Historic Learning Center (MISHLS) at Building 640, the original site of the US Army’s first language school in the Presidio of San Francisco. Today, this adaptive reuse project was established in 2013 as an Interpretive Center and serves as a energizing source for MIS in WW II history and as a multi-cultural space of discourse on civil liberties and justice issues world-wide.