Deported to War Zones

When the German government learned that some of its overseas citizens had been seized in Latin America and interned in the United States, it ordered the seizure of U.S. and Latin American citizens living in Europe. Complex negotiations followed, resulting in several exchanges of civilian prisoners.

The State Department policy was to exchange only harmless people of German or Japanese ancestry. The U.S. did not want to return aliens who might aid the Axis war effort. Repatriates to Germany signed an oath not to perform military service. Some died as civilians, killed by Allied bombs. Others, suspected by German authorities of being U.S. spies, were imprisoned.

“What would I do in Germany? Everything there was destroyed. My parents were dead. I had nothing there… My wife, my children were…in Guatemala. I wanted to…come back right away and start working again.”

— Hugo Droege, German internee who was sent to Germany against his will.

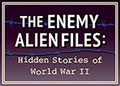

Registration of German U.S. residents during their return to Germany in an exchange for U.S. civilians and POWs, ca. early 1940s. Courtesy of Arnold Krammer.

“The exchange took place…in early February 1945… [We] were brought to the border on the back of a flatbed truck in small groups. We waited for hours in the cold until it was our turn to cross… We slowly made [our] way…amidst bombings…we had to walk because the railways were destroyed… Within two weeks…the Gestapo arrested father and took him away to an unknown prison, suspecting him of being an undercover spy… We did not know if he was alive until the end of the war.”

— Ensila Eiserloh Bennet, German internee recalling her childhood deportation experience.

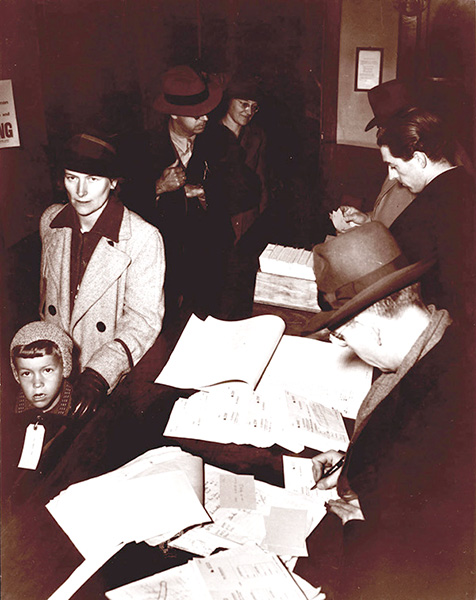

Japanese Peruvian boys wearing ID tags being processed for deportation, ca 1943.National Archives.

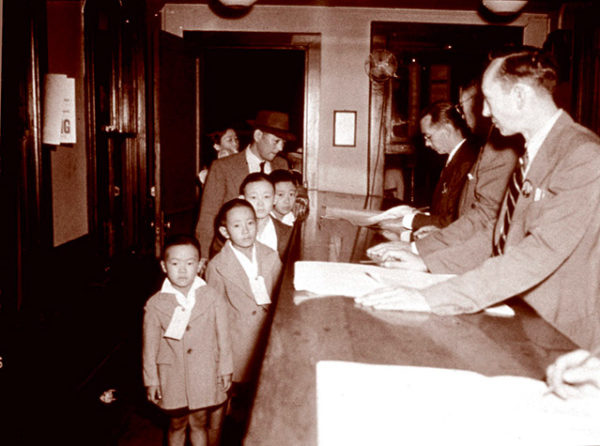

A soldier and two other men lift an elderly Japanese man onto the train platform for deportation, ca. 1943. National Archives.

From 1942 to 1945, at least 2,000 persons of German ancestry and at least 37 Italians, including women and children, from the U.S. and Latin America were sent to Europe in at least six exchanges across the Atlantic Ocean at the height of the war. Two Swedish ships – the Gripsholm and the Drottningholm – were used to transport “enemy aliens” to Europe.

The neutral Swedish flagged MV Gripsholm transported approximately 4,800 civilians of German and Japanese ancestry from the U.S. and Latin America to the war zones of Europe and Asia in exchange for U.S and Latin American civilians and prisoners of war held by Germany and Japan. There were at least six exchange trips with Germany and two with Japan. National Archives.

Japan also agreed to prisoner exchanges, which took place at Portuguese ports in India and Africa. But Japan soon discovered that the U.S. was not returning the Japanese nationals requested. Japan was concerned about reports of forced repatriation. Japan did not want to accept “repatriates” who did not want to return. There was also difficulty in finding ships. Two exchanges occurred using the Gripsholm in 1942 and 1943 involving more than 2,800 persons of Japanese ancestry, some of whom were citizens of the U.S. or Latin American nations. Some deportees were drafted into the military service of Japan and died in combat. Others lost their lives in air raids as civilians. The United States conducted a search for Japanese nationals in Belgium, Romania, Italy and elsewhere, but negotiations for further exchanges failed.

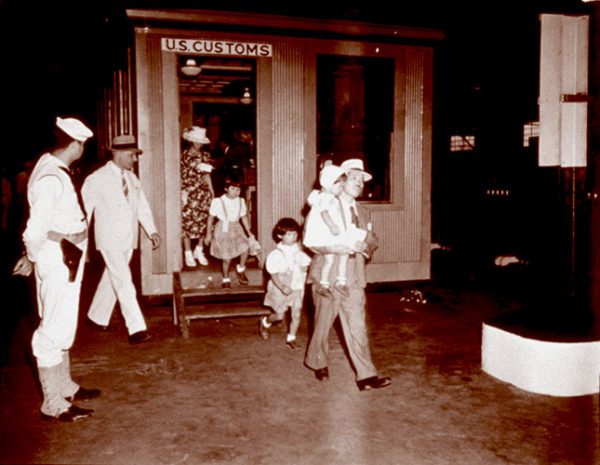

A Japanese family walking out of a U.S. customs booth, ca. 1943. National Archives.

These Japanese men are tagged and being prepared for exchange, ca. 1943. National Archives.

Double file line of Japanese Peruvian men walking, followed by armed MPs, New Orleans, Louisiana, ca. 1943. National Archives.

“My grandparents owned a department store in Callao, Peru. And during WWII, they were among the first Japanese Peruvians to be taken hostage. They were used in one of the exchanges for American civilians… We never got to see them again.”

— Rose Shibayama Nishimura, Japanese Peruvian internee.