Release, Resettlement and “Repatriation”

Alien internees were released during and after the war under various circumstances. In October 1942, Italians were removed from the “enemy alien” classification, and evacuees were allowed to return to the prohibited zones from which they had been removed. However, internees and excludees were not permitted to return to their homes until late 1943, after Italy surrendered. Most returned to their communities quietly, with few of their neighbors aware of where they had been.

Late in 1942, the Department of Justice began to review the cases of interned Jews and anti-Nazis, due partly to pressure from the U.S. Jewish community, Catholic groups, and the American Civil Liberties Union. By April 1943, most were granted a parole status called “internment at-large.” At least 16 of those paroled were then drafted or volunteered for the U.S. Army. The last of the 81 Jews from Latin America were freed in 1946. During and after the war, 74 of them chose to remain in the United States.

Preparing for deportation to Japan, “repatriates” and expatriates, including renunciants, assemble at the high school auditorium at Tule Lake Segregation Center in California, December 27, 1945. National Archives.)

Agents searching a “repatriate,” Seattle, Washington, November 24, 1945. National Archives.

The Alien Enemies Act only permitted internment for the duration of the war. Two months after the European hostilities ended in May of 1945, President Harry Truman issued Presidential Proclamation 2655 ordering the deportation of “dangerous enemy aliens” who were still interned. Thus, many Germans and their U.S. citizen families were involuntarily “repatriated” to war-devastated Germany and left there to fend for themselves. Germans who did not want to repatriate remained interned and fought desperately for years to avoid being deported. By mid-1948, the camps were empty, but the last German internee was not released until 1949 (from Ellis Island). Some had been interned for nearly seven years. For many, the internment nightmare began and ended at Ellis Island. Known for welcoming immigrants, it was used longer than any other facility for internment.

“[We] landed at Uraga port in Tokyo Bay… We went to a distant place, on foot, to find someone who would exchange food for clothing, and also to river banks to gather grass to satisfy our empty stomachs.”

— Mitsuaki Oyama, Japanese Peruvian internee who was deported to Japan at the end of the war.

“Repatriates” to Japan boarding a ship docked in Seattle, Washington, November 24, 1945. National Archives.

Most internees had a very difficult time re-entering society after their long incarceration. They had lost their homes and belongings and could not go back to their old jobs. Many were stigmatized, particularly in the many communities where their internment was well-publicized. Others, particularly children, had their educational and economic opportunities seriously curtailed. Most internees never completely made the transition back to the life they had before government agents first knocked on their doors. Deportees trying to return to the United States or Latin America had an even more difficult time surviving in war-devastated countries, with most unable to return to their homes and businesses.

With Japan’s formal surrender in September of 1945, Truman issued Presidential Proclamation 2662, authorizing the State Department to deport the Latin American internees and anyone else still deemed “dangerous.” However, most Latin American governments initially refused to re-admit the internees of Japanese ancestry. Peru allowed only 77 internees of Japanese ancestry – all Peruvian citizens or married to citizens – to return in 1946. Thus, between November 1945 and June 1946, at least 945 Japanese Peruvians and 112 other Japanese Latin Americans were deported to war-devastated Japan.

“Finally, in 1947, we were shipped [from Crystal City] to Ellis Island… I spent too much time facing the back of the Statue of Liberty. I always felt that even though she had welcomed immigrants promising the American Dream, she turned her back on us just because of our ancestry.”

— Eberhard E. Fuhr, German internee who lived in Cincinnati, Ohio.

More than 300 Japanese Latin Americans decided to remain in the United States and fight deportation. Attorneys Wayne Collins and Ernest Besig of the Northern California American Civil Liberties Union successfully halted the deportations. These internees were granted parole out of camp, with some being sponsored by Japanese American relatives or churches. Over two-thirds were released to an economic guarantor such as Seabrook Farms, a frozen-food processing plant in New Jersey, which welcomed them as a source of cheap labor. Seabrook Farms also recruited U.S. resident Japanese and German aliens (and German POWs) for this “relaxed internment.” The Japanese from Peru remained in legal limbo until the 1950s when a change in the immigration law allowed all Latin American internees to apply for legal residency.

Women packaging peas at Seabrook Farms, New Jersey. Courtesy of Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center.

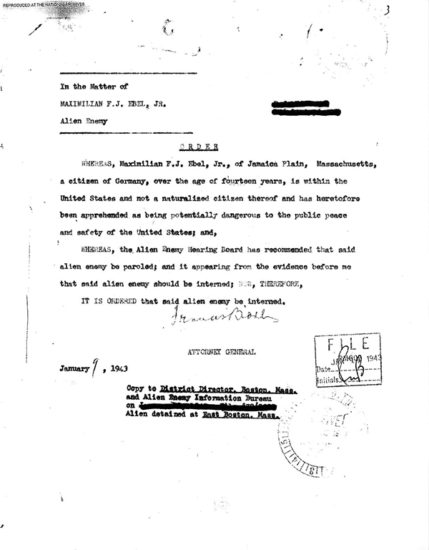

“This Board believes that this alien’s further internment is unjustifiable; that he is in no sense disloyal to this country…and that he ought to be released.”

— Release recommendation for German internee Max Ebel after 1-1/2 years of internment made by the Rehearing Board, Bismarck, North Dakota on April 13, 1944. Ebel was finally paroled in June of 1944.

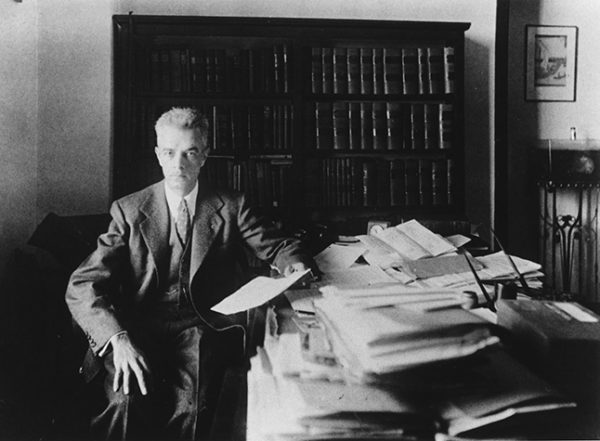

Wayne Collins, Northern California ACLU attorney, halted the post-war deportation of over 300 Japanese Latin Americans and for 20 years fought tirelessly to restore the U.S. citizenship of nearly 5,000 Nisei renunciants, ca. 1942. Courtesy of Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Wayne Collins also took on the cause of nearly 5,000 “renunciants” – young Nisei who were manipulated by the U.S. into renouncing their U.S. citizenship, becoming “enemy aliens” who were vulnerable to deportation. Some 3,500 Issei and renunciants were deported to Japan. But those who wished to reclaim their citizenship and stay in the U.S. had to press their cases through an appeals process managed by the U.S. Department of Justice. The last case was not settled until 1968.

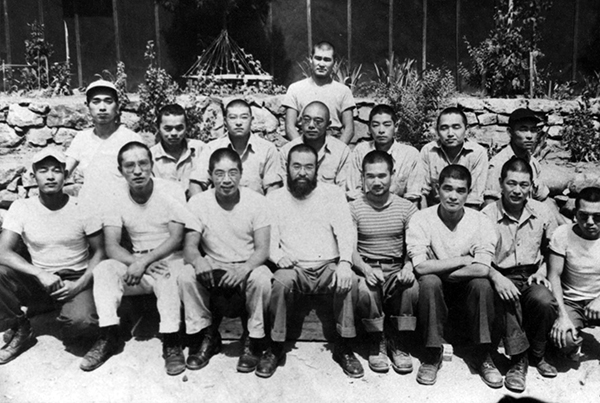

Tule Lake renunciants at Santa Fe alien internment camp in New Mexico, ca. 1945. Courtesy of John Christgau.

At war’s end, there were still a thousand German deportees in U.S. camps petitioning to return to their homes in Latin America. Peru and most other Latin countries were willing to take them back on a case-by-case basis. The State Department tried for two years to send them all to Germany, where they would come under the authority of the Allied occupation forces. But eventually, U.S. courts, the Justice Department, and Latin American governments agreed that they should be released to their former countries of residence.

Bronzini family and friends at a dinner party in Castro Valley, California, after the armistice had been signed with Italy. Former Italian POWs are in uniform, ca. 1943-44. Courtesy of Velio Alberto Bronzini.