Axis Powers Rising

Germany’s economy was devastated by World War I (WWI) and by the reparations the victors extracted afterward. Italy also suffered widespread chaos in the post-war period, leading to the rise of Benito Mussolini and his fascist government. Aggressive foreign policies by both nations began to alarm world leaders in the 1930s. But many in Britain and the U.S. remained isolationist, hoping to avoid involvement in another catastrophic war.

Early in his career, Mussolini was a popular and admired figure, someone of whom Italian Americans could be proud. The world press portrayed him as a hero – the first modern leader to lift his nation out of post-WWI chaos and Depression. But when Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, respect changed to widespread revulsion.

German He 111 bombing Warsaw, Poland in 1939. Luftwaffe (German Air Force) Photo. Wikimedia Commons.

The expansion of fascism by Nazi Germany increasingly alarmed the U.S. and its allies, especially when Hitler’s armies invaded Poland in 1939 and continued their rapid march into neighboring countries with resistance quickly overcome. When Italy, a U.S. ally in WWI, joined Germany’s invasion of France in June of 1940, President Roosevelt condemned Mussolini for striking a “dagger” into “the back of his neighbor.” The following spring, the U.S. State Department ordered all German and Italian consulates in the U.S. closed.

Hitler and Mussolini in Munich, Germany, June 1940. Eva Braun’s photo albums, seized by the U.S. Government. National Archives.

When Germany declared war on Britain in September 1939, the U.S. passed lend-lease legislation to support Britain’s war effort. German submarines in the Atlantic began to sink U.S. merchant ships. As German and Italian (Axis) belligerence became more blatant and the fall of Europe appeared inevitable, it seemed that the United States might once again be drawn into war.

Meanwhile, Japan’s takeover of Manchuria and its pursuit of other Asian land and resources caused the U.S. to see Japan as a threat to U.S. interests in the Pacific. Many Japanese politicians opposed and feared war with the United States and believed that Britain would eventually defeat Germany. Even so, Japan allied itself with Germany and Italy in 1940, signing the Tripartite Axis Pact. Japanese politicians expected this pact to deter any strong U.S. action against Japanese aggression in Asia. But extreme nationalists in the Japanese military prevailed, and Japan’s attack on the U.S. naval installation at Pearl Harbor, Hawai’i, precipitated U.S. entry into the Pacific war.

Japanese tanks rumbled through Nanking on the morning of December 13, 1937. (New China News Agency), Bettmann/Getty Images.

International Insecurity – Latin America

Prior to WWII, the Roosevelt Administration was concerned that fascist influence in Latin America would endanger U.S. national security. Over one million ethnic Germans lived in the region, concentrated in southern Brazil, Argentina and Chile, and dispersed throughout South and Central America. War planners in Washington believed that the Germans in Latin America posed an even greater security threat than Germans in the United States.

U.S. code-breaking and other intelligence-gathering efforts revealed espionage and subversive activities by German agents related to incidents such as U-boat attacks on ships in the Atlantic and coup attempts in Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, and Bolivia. Italy and Japan also conducted espionage in Latin America before and during the war. In addition, British intelligence agents engaged in propaganda and document forgery to persuade the U.S. to aid Britain and enter the war. Hence, U.S. government concern over national security threats – both real and manufactured – helped place German, Japanese, and Italian immigrants under suspicion.

With evidence of Nazi involvement in coup attempts, Washington officials expanded its intervention in the affairs of Latin American nations. Of the nearly 100 meetings of the joint planning committee of the State, Navy, and War Departments in 1939 and 1940, all but six had Latin America at the top of the agenda. By blacklisting and expelling Germans from Latin America, Washington hoped to destroy “the nuclei of Axis infection.”

Imperial Japan’s expansion in Asia and alliance with Germany inflamed existing anti-Japanese sentiment in Latin America. In 1936, for example, Peru restricted Japanese immigration through quotas and stopped granting naturalization papers to Japanese immigrants. An anti-Japanese campaign waged in the press fanned the flames of resentment over Japanese economic competition, framed as a purported military threat. In 1940, Peru proposed new laws to prohibit Japanese ownership of land and ban further immigration.

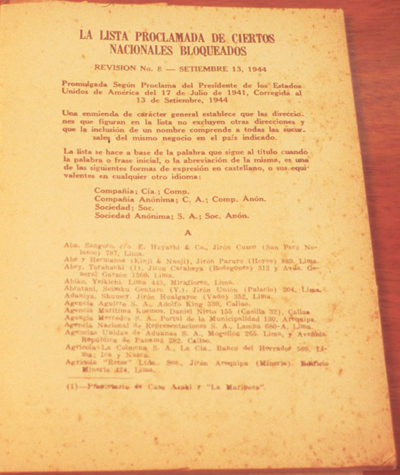

The U.S. government called for summit meetings to discuss common responses to the Axis menace, and many Latin American governments readily participated. In December 1938, U.S. and Latin representatives met in Lima and passed a resolution to deny minority rights to foreign ethnic groups and oppose political activity by foreigners.

One of many propaganda posters used to rally Latin American sentiment against Axis powers. Latin America is portrayed at the mercy of an outside menace. National Archives.

Blacklists and Backroom Deals

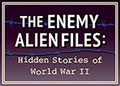

Long before Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government began contingency planning for the eventuality of war. In 1936, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) started compiling lists of “dangerous persons” such as Japanese Buddhist or Shinto priests, prominent business/cultural leaders in the German, Italian, and Japanese communities, and members of Nazi and fascist groups in the U.S. Similar lists had been prepared just before WWI, and were used to identify and intern over 6,000 German aliens.

In 1939, the FBI, War Department, and Navy began coordinating investigation of espionage and sabotage. The FBI and the Special Defense Unit of the Department of Justice compiled a Custodial Detention Index of “potentially dangerous” Germans, Italians, communist sympathizers, anti-fascists, pro-fascists, and pro-Nazis to be arrested if the United States entered the war. Many got onto such lists due to “tips” from informants with grudges, or neighbors who simply thought people suspicious because of their accents or “foreignness.”

The Federal Alien Registration Act of 1940 (“Smith Act”) required all aliens to register, be fingerprinted, provide information about their membership in organizations, and report regularly to designated authorities. This Act, along with the illegal use of U.S. census data, made it possible to later locate and identify non-citizens. The FBI maintained a “Suspected Organizations List” for Italians, Germans, and Japanese in the U.S. By spring 1941, the Department of Justice had developed procedures to detain and indefinitely intern aliens and “potentially dangerous persons.” In October, the Departments of Justice, State, and War began to meet collectively to map out internment strategies.

Throughout the late 1930s, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover pressed for greater FBI involvement in international intelligence and authority to investigate non-citizens. In 1939, FBI agents were sent to Latin America for surveillance of Axis nationals. By 1941, FBI agents were posted at U.S. embassies in Latin America as “legal attachés” or assigned to local/national police forces as liaison officers to collect information on German, Italian, and Japanese immigrants.

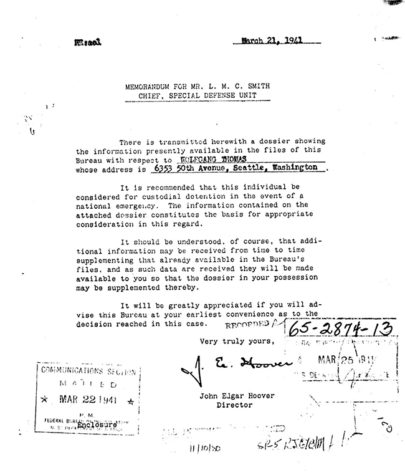

The “Proclaimed List of Certain Blocked Nationals” was issued in July 1941 by the State Department to prohibit U.S. trade with all Latin American businesses suspected of being pro-Axis. The criteria were so broad that they could apply to anyone of German, Italian, or Japanese origin. The United States was especially concerned about German inroads into Latin American markets and considered German economic competition to be a security risk. U.S. officials believed that the success of German political and military interests in the Americas rested with the German residents of Latin America. The blacklist was intended to crush their economic strength, depriving them of resources that might be used for propaganda or to fund subversion and, at the same time, deal a blow to a major trade rival.

In October 1941, the United States and Panama entered into an agreement to apprehend and intern Axis nationals in Panama if the U.S. declared war on any Axis country, with the U.S. assuming all expenses and responsibilities for their internment. This U.S.-built military camp in the Panama Canal Zone became a detention center for the transfer of Japanese, Germans, and Italians to camps in the U.S.

President Roosevelt welcomes Peruvian President Manuel Prado to Washington, D.C., 1942. Peru readily agreed to deport “enemy alien” residents and some Peruvian citizens to the U.S. and became one of the largest recipients of U.S. military and economic aid in Latin America under the Lend-Lease Program. National Archives.

;