THE UNITED STATES

Immigrants come to the United States for a variety of reasons. Some are driven from their home countries by political turmoil, poverty, climate change, and religious or social persecution. Others are drawn here by perceived economic opportunity, adventure, or the prospect of the rights, protections, and freedoms of democracy.

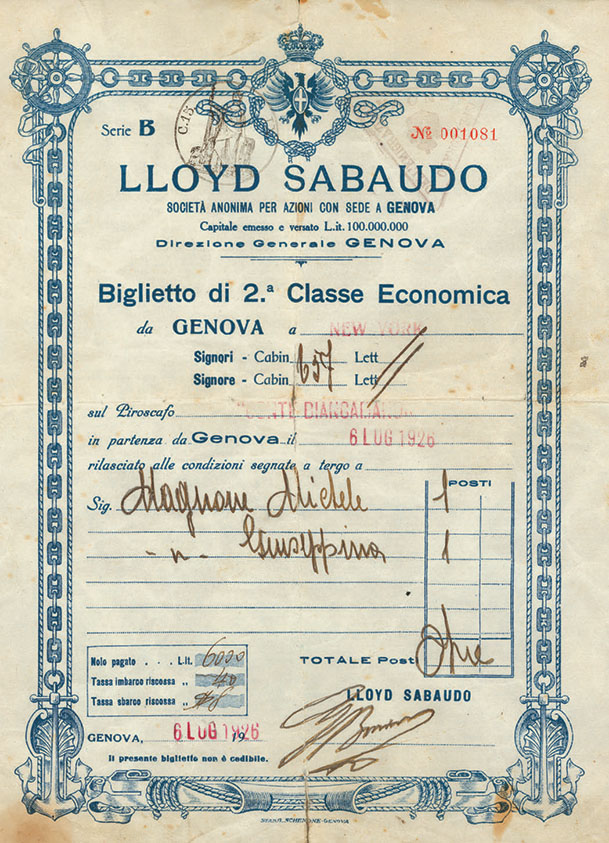

Italian and German immigrants began arriving in large numbers in the 19th century, with influx to the American West beginning during the 1850s California Gold Rush. By 1940, these nationalities constituted the two largest foreign-born groups in the U.S. Like most immigrants, they formed ethnic organizations that provided comfort to those far from their homelands.

Japanese immigration to Hawai’i for plantation labor began in 1868. Japan permitted Okinawan overseas emigration in 1899, following the Japanese military annexation of the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1879, its incorporation as the Okinawan Prefecture, and forced assimilation policies. Okinawans faced discrimination and stigma both in Japan and in overseas Japanese communities. Later, many Japanese and Okinawans went on to the U.S. mainland, mostly California, where they farmed and started businesses, often serving the growing Japanese communities.

“I put down roots in the land of Peru, and with my life’s blood nurturing the soil… Deep are my feelings for the Latin country I call my ‘second motherland.’”

— Seiichi Higashide, Japanese internee from Peru.

“My father Guido worked for five years in America saving up enough money, and as promised, he returned to Italy to marry his childhood sweetheart, my mother Clara… He would say to his family, ‘L’ho trovato l’America. I’ve found America.’ America was all that he had dreamed it would be.”

— Velio Alberto Bronzini, son of Italian immigrants who had to close their produce market in Oakland, California, because it was located in a restricted zone.

LATIN AMERICA

Japanese immigrants began arriving in Latin America in the late 1890s. In 1899, Peru started drawing labor from Japan for agriculture, mining, and industry. Asian migration to the U.S. was becoming more difficult due to racism, discriminatory immigration laws, and the cancellation of Hawaiian labor contracts, causing many to look instead to Latin America. By 1923, three emigration companies had transported 17,764 Japanese and Okinawans to Peru.

Large-scale German immigration to Latin America began in 1848 after a failed liberal revolution that attempted to unify various German states. Larger waves followed in the 1880s, 1890s, and after World War I.

Italians came to Latin America in numbers comparable to the millions emigrating to the U.S. Particularly in Argentina, they settled fairly comfortably into the dominant Catholic, Latin-based culture.

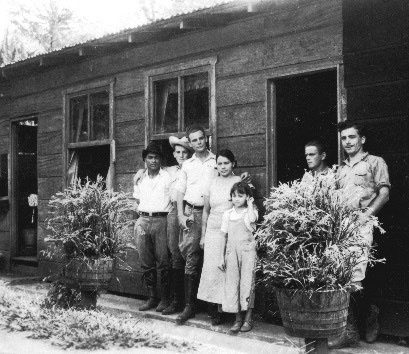

Cultivating Communities

Japanese settlement in North America concentrated in Hawai’i and along the U.S. West Coast. However, due to discriminatory laws, Japanese immigrants to the U.S. were largely restricted to ethnic enclaves and relegated to menial labor on plantations and farms. Some were able to establish niches in farming, fishing, and ethnic small businesses. Despite education, their U.S.-born children faced limited economic opportunities in mainstream society.

By 1940, there were about 26,000 persons of Japanese and Okinawan ancestry in Peru. About 17,000 were Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) and 8,800 were Nisei (second generation children of Issei). The Issei represented 29% of the foreign-born population of Peru. Ninety percent of them lived in urban areas along the coast and were involved in a wide variety of jobs: farm labor, coffee/cotton growing, small business (café, barbershop, bakery), rubber production, poultry farming, hosiery and hat making, plumbing, carpentry. They were florists, chauffeurs, hotel owners, restaurateurs, peddlers, merchants, glaziers, jewelry makers.

The Japanese Peruvian community developed a rich social and cultural life. There was increasing immersion in Spanish-Catholic traditions, along with retention of Japanese culture, including Japanese language schools and newspapers, food, athletic organizations, and prefectural societies. Trips to Japan were encouraged, especially for teenage boys, and brides were often brought over from Japan.

“As Americans, we originally came from many different shores, and our diversity has been at the center of the making of America.”

— Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America.

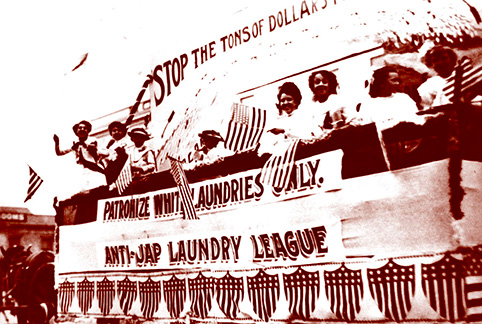

By 1941, 127,000 Japanese Americans lived in the U.S. Although Japanese Americans were only one percent of the California population, they controlled almost half of the commercial truck farming. Anti-Japanese rhetoric and actions increased in proportion to their economic success, both in the U.S. and Latin America.

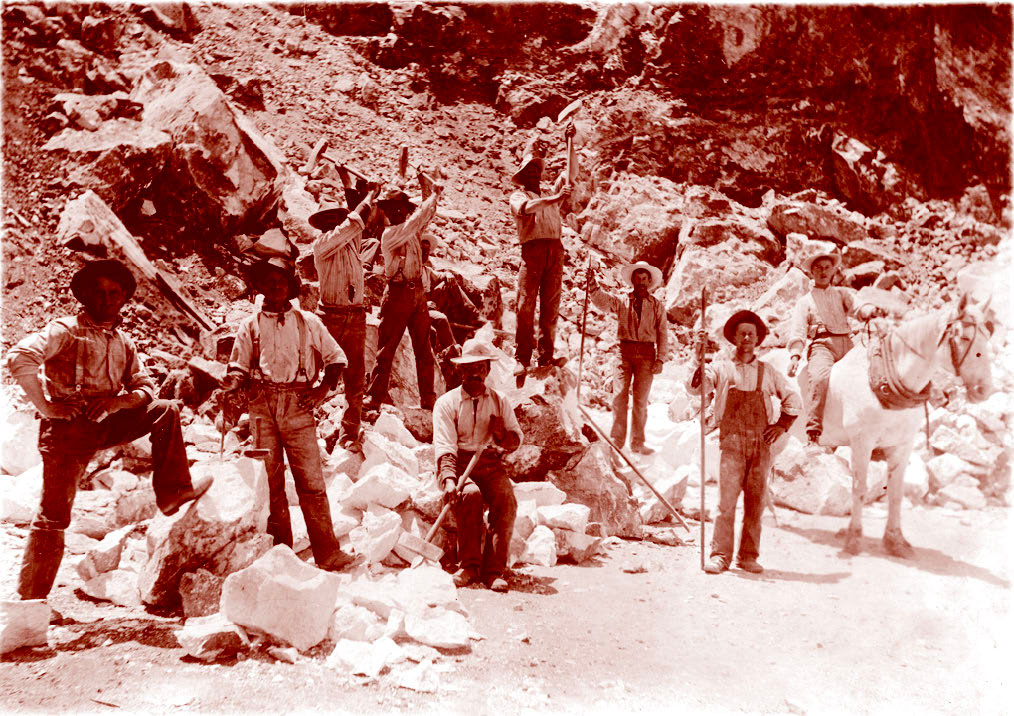

Italians, like most immigrants, were drawn to the United States by economic opportunities. The majority were concentrated in large cities in the eastern half of the country where they created ethnic enclaves known as “Little Italy.” Many worked as laborers constructing the New York subway system, and the roads and buildings in burgeoning cities. Some worked their way across the country and settled along the West Coast where they fished, worked in quarries and mines, and hauled refuse. When they could, they bought land and planted artichokes, fruit orchards, and vineyards. By 1940, Italians made up the largest foreign-born group in the United States.

Sticks and Stones and Words that Hurt

While immigrants’ labor is often needed by their host country, their presence may be resented. Newcomers who are easily distinguishable from the surrounding community residents – due to physical characteristics, language, dress, and customs – often become targets of racism, anti-immigrant attitudes, and discrimination.

The United States has a long history of anti-Asian racism and legislation. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 signaled a change in the nation’s immigration practices. For the first time in U.S. history, members of a specific nationality were refused entry and admittance to the naturalization process. A 1908 “Gentleman’s Agreement” restricted new immigration from Japan. Issei were prevented by law from becoming citizens, owning land, or living in certain neighborhoods. The Immigration Act of 1924 prohibited the entry of aliens ineligible for citizenship, essentially halting all Asian immigration. As a result, immigration from Japan shifted from North America to Latin America.

“Racial animosity also extended to children. After school one day, I encountered a redheaded upper-classman from the Central Elementary School. Though we did not know each other, he seemed hostile. ‘Jap,’ he sneered.”

— Clifford I. Uyeda, son of Japanese immigrants, Suspended: Growing Up Asian in America.

In Hawai’i, Peru, and California, tension resulted from racism, job competition, wage differentials, and communication problems due to language differences. The Japanese were often portrayed as unassimilable and “inscrutable.” They were sometimes physically attacked. The popular media played to jingoist fears of “yellow peril, Japs, and Chinks.”

Germans and Italians also experienced discrimination, name-calling – “krauts, huns, wops, dagos” – and acts of violence. During World War I, when Germans were also labeled “enemy aliens,” Lutheran churches and German books were burned. U.S. citizens and residents of German ancestry were persecuted to such an extent that many changed their names to disguise their ancestry, and dissolved their ethnic organizations.

Italians were met with widespread discrimination, and were often employed at lower pay rates than other ethnic groups. American “nativists” treated them as virtually another “race,” with inborn tendencies to anarchy and crime. This sort of bias played a large part in the infamous Sacco-Vanzetti murder trial of 1920. In 1924, anti-Italian prejudice culminated in an immigration law that severely limited legal immigration from Italy.

“The mob broke into shops, looted their merchandise, and utterly vandalized facilities…the mob even used trucks to ram down the shutters…even homes of individual Japanese were attacked… They had fled their homes with only the clothes on their backs and with only desperate efforts had escaped with their lives.”

— Seiichi Higashide, Japanese internee from Peru

In Latin America, the Germans, Italians, and Japanese presented economic competition to the dominant population and to the United States, which considered the region to be “our backyard.” In 1940, Peruvians rioted against the Japanese communities in Lima and Callao, where about 600 businesses, schools, and homes were seriously damaged and looted, leaving ten Japanese dead and dozens injured.