Latin America

As war spread in Europe and Asia, Roosevelt administration officials became concerned about potential military, political, and economic threats to U.S. national security from south of the Rio Grande. Entire communities of German, Japanese, and Italian expatriates in Latin America came under suspicion of secretly organizing to carry out sabotage throughout the Western Hemisphere. To preempt subversion in the “soft underbelly” of the Americas, Washington orchestrated the seizure and internment of 4,058 Germans, 2,264 Japanese (about one third of whom were Okinawan) and 288 Italians from 18 Latin American countries.

Placement on the lists for deportation was based on suspicion alone, according to John Emmerson, Third Secretary to the U.S. Embassy to Peru: “Lacking incriminating evidence, we established the criteria of leadership and influence in the community to determine those Japanese to be expelled.” This meant teachers, priests, journalists, business owners, or anyone who held a position in the many prefecture clubs or cultural organizations.

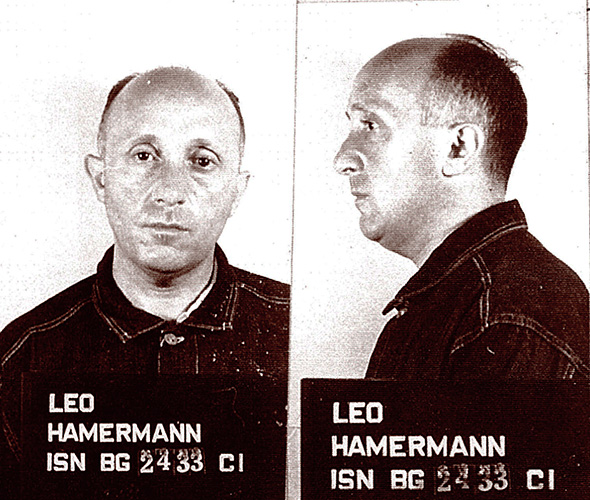

Leo Hamermann, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, was deported to the U.S. by Bolivian officials who had no evidence against him but were anxious to please the U.S. government. National Archives.

“The [Peruvian] police came looking for [my father] several times, and after not finding him, they arrested my mother and placed her in jail to force my father out of hiding. Our oldest sister, who was 11-years-old, went with her, because she did not want our mother to be alone. When word of this reached my father, he gave himself up.”

— Rose Shibayama Nishimura, Japanese Peruvian internee.

Japanese “enemy aliens” being checked before boarding train, Kenedy alien internment camp in Texas, August 1943. National Archives..

“In February 1943…some Peruvian police came and arrested my employer. My employer pulled a fast one by bribing the police and offered me as a substitute… I do not know why I was arrested, as I had done nothing wrong. I was taken to a jail in Lima.”

— Arthur Shinei Yakabi, Japanese Peruvian internee.

Starting in July 1941, newspapers in nearly every Latin American country published “La Lista Negra,” the informal name for what the United States called “The Proclaimed List of Certain Blocked Nationals.” The U.S. and Latin American governments updated the lists of companies and individuals to boycott throughout the war. Intended to deny funds to the Axis powers, the blacklist also affected people with no connection to the war effort. Businesses folded and some families never recovered from the economic damage inflicted.

On the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, local police in Latin America began apprehending “potential subversives.” None of them were charged with a crime. There were no search warrants issued, no hearings given. Axis nationals were taken to local jails until they could be transported to the U.S. Wives and children were left behind to fend for themselves. Some families chose to go into internment with their deported head of household rather than be separated.

Among the Germans seized were 81 Jews purported to be Nazi agents, or who were turned in for bounty money, or taken simply because they were German.

Koshio Henry Shima (second man on the right, looking at the soldier) and other Japanese Peruvian detainees arriving in Panama in transit to the U.S. for internment, January 1943. Koshio Henry Shima Collection. Courtesy of the University of Idaho’s Asian American Comparative Collection. National Archives.

Wanted: Hostages to Exchange

Washington had additional motives for interning Japanese, German, and Italian nationals from Latin America. As early as 1939, the U.S. State Department began to consider the fate of American citizens living abroad and develop plans to ensure humane treatment and return of U.S. civilians caught in war zones.

Thus, U.S. citizens and aliens of Japanese, German, and Italian ancestry living in the United States and Latin America were to be exchanged for other U.S. citizens. Washington seized Axis nationals from Latin America as hostages to barter for the return of U.S. citizens. Secretary of State Cordell Hull advised hemispheric removal of Axis nationals in an October 1942 memo to President Roosevelt:

“…I propose the following course of action: …

1.) Continue our exchange agreement with the Japanese until the Americans are out of China, Japan and the Philippines – so far as possible…

2.) Continue our efforts to remove all [the Japanese from these American Republic countries for internment in the United States.

3.) Continue our efforts to remove dangerous Germans and Italians still there, together with their families…” (emphasis added)

By December 18, 1942, General George Marshall issued a secret order to the Caribbean Defense Command outlining procedures for the deportation of Japanese and German aliens from Latin America. He stated that, “These interned nationals are to be used for exchange with interned American civilian nationals.”

“We were all taken to the small basement of a police station. No one could sleep that night because of the crowded conditions, cigarette smoke and heat. There were no chairs or beds, only a cement floor. We could not lie down because there wasn’t enough room. Early next morning we were loaded onto three open trucks and told we were being taken to an unknown destination.”

— Ginzo Murono, Japanese internee from Peru.

Among the Latin American governments, the degree of cooperation or resistance varied greatly. Peru became the most enthusiastic participant in the hostage exchange program, with some government officials advocating wholesale removal of its entire Japanese population. Peru sent nearly 1,800 persons of Japanese ancestry to the U.S.

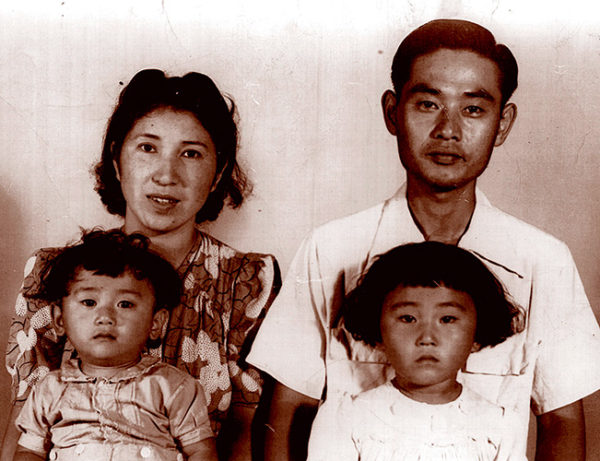

The Murono family, deported from Peru, pose for an identification photo at the Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas. They remained there for two years, ca. 1943. Hisako Murono Collection, Courtesy of Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center.

Economic Motives

The 1930s saw a spectacular expansion of the German economic presence in Latin America, at the direct expense of U.S. interests. When the U.S. became concerned about espionage and pro-Axis propaganda arising in the German, Japanese, and Italian communities of Latin America, little distinction was drawn between military and economic aims in the quest for national security.

Various forms of U.S. diplomatic pressure, ranging from enticements to economic coercion, were used to obtain Latin American cooperation. In July 1940, the U.S. agreed to help improve the efficiency of the Peruvian Navy and aviation program, and later sent advisors to Peru’s army. A January 1942 lend-lease agreement secured a U.S. military presence in northern Peru in exchange for arms and munitions.

The United States and its Allies engaged in preemptive buying of strategic materials on the world market, denying supplies to the German and Japanese war machines. Reciprocal trade agreements for raw materials, especially minerals, and massive commodity purchases from Latin American countries helped convince them to cooperate with the U.S. deportation program.

In several cases, individual deportees were clearly targeted because of their important economic role in their countries of residence, even when there was no evidence that they had assisted the Axis. Some German nationals who spent the war in internment camps were simply businessmen whose firms competed with American interests. Some of the deportees were expelled, especially by the dictatorships ruling most of Central America and the Caribbean, so that their property could more easily be seized.

“[The Proclaimed List] is a policy designed by us [the United States] to secure the commercial and financial annihilation of persons resident in and doing business in accordance with the laws of the American republics and against whom we feel that those republics will take no action.”

— Philip Bonsal, Chief of Division of American Republic Affairs, State Department in a memo to Undersecretary of State, Sumner Welles, Jan. 1942.

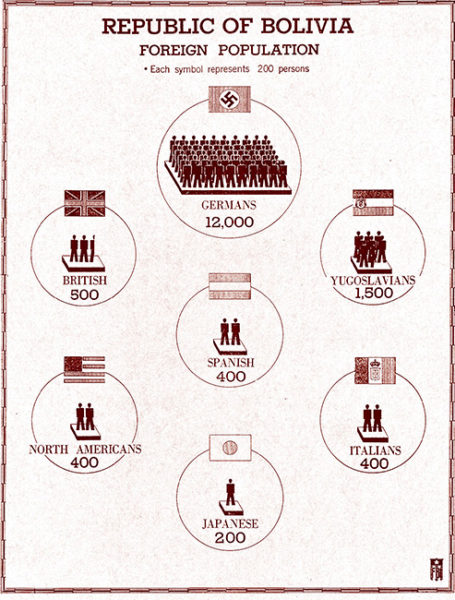

Many official U.S. studies conducted on Latin America portrayed the German population there as a serious threat. This FBI study labels the 12,000 Germans in Bolivia as “Nazis,” when 8,500 of them were Jewish refugees. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.