“Enemy Alien” Registration, Curfews, & Restrictions

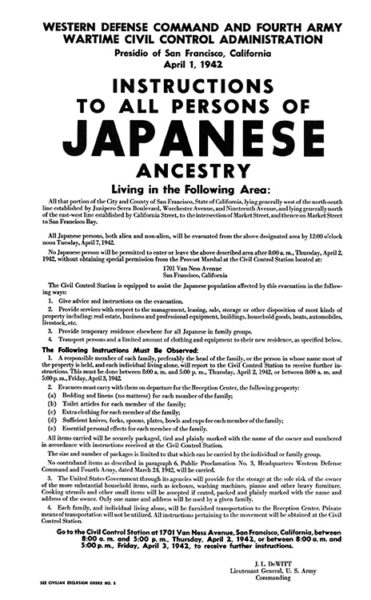

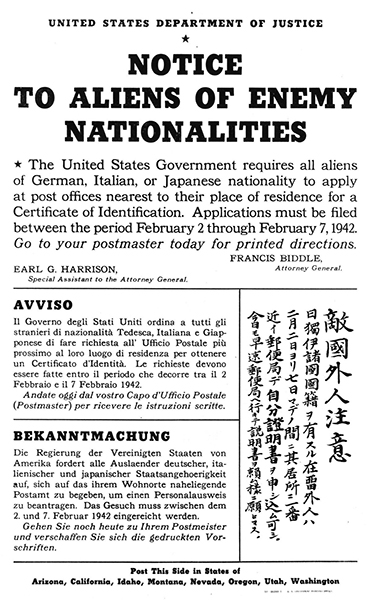

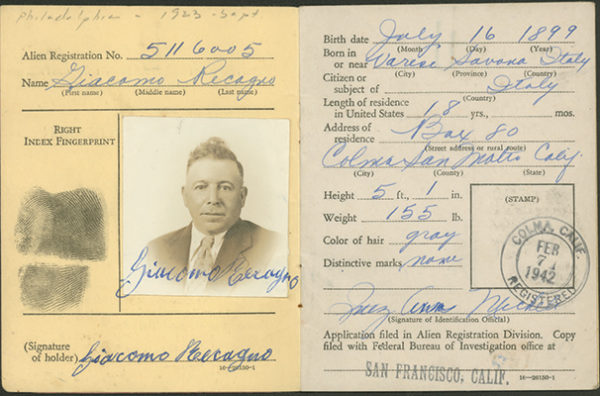

In January 1942, pursuant to the December Presidential Proclamations, the Justice Department ordered all Japanese, Italian, and German aliens residing in the U.S. to re-register at local post offices around the country, and be fingerprinted and photographed. They were required to carry photo-bearing “enemy alien” Certificates of Identification at all times.

“Enemy aliens” were ordered to turn over “contraband” to local police. Prohibited items included all firearms, short-wave radios, cameras, and “signaling devices” such as flashlights. FBI agents searched homes and confiscated this type of personal property, much of which was never returned. Ownership of such property could later be grounds for internment. The Coast Guard requisitioned fishing boats belonging to Italians and impounded boats of Japanese fishermen, depriving many of them of their livelihood.

In addition, all “enemy aliens” in the Western Defense Command were subject to a curfew between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. daily and were not allowed to travel more than five miles from home unless a travel permit was applied for and granted. Often, parents could not visit their children in hospitals, attend funerals, or visit relatives more than five miles away.

Alien registration notice posted by local governments, 1942. Courtesy of Japanese American National Library.

“Going back to school was really difficult. Few of our friends wanted to have contact with us. One girl refused to go out with [my brother] because she ‘didn’t go out with Nazis.’ A good family friend parked a block away when he came to visit. We even felt like outcasts with our own church because of our German blood. Many were afraid of associating with us because it might mean they, too, would become suspects of the FBI. Fear ran rampant.”

— Guenther Greis, son of a German internee who was arrested in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

“You came to the U.S. to bomb bridges, didn’t you?” “No,” I say. “I came to wash windows!”

— Joe Cervetto, Italian immigrant recalling his arrest and interrogation by police in San Francisco, California.

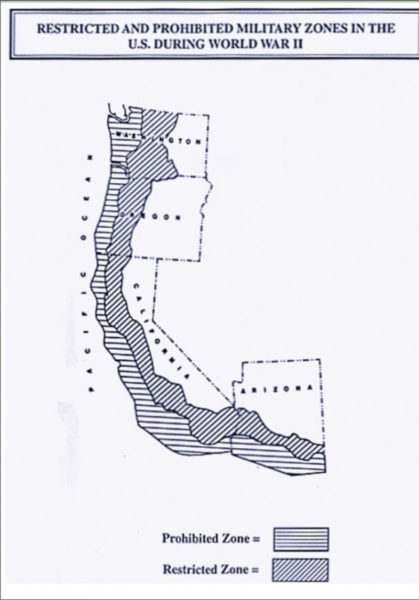

PWest Coast Military Zones Map, 1942-1945. Adapted from U.S. War Dept. Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942. Courtesy of University of Denver.

In March 1942, Executive Order 9095 established the Office of the Alien Property Custodian, which had complete authority over alien assets. Many aliens’ assets, such as bank accounts, were frozen, making life even more difficult for those affected.

The impact of these restrictions was widespread and apparently unanticipated by the government. In California communities like Monterey, Santa Cruz, Pittsburg, and San Francisco, Italians constituted a majority of the fishermen, garbage collectors, restaurant workers, and janitors. The majority of West Coast truck farmers were Japanese. The restrictions created serious employment and food-supply problems for the general public, as well as for the immigrants and their families.

Alien Certificate of Identification of Giacomo Recagno, San Francisco, California, 1942. All “enemy aliens” had to carry this ID. Courtesy of Italian American Collection, San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Similar restrictions on Axis nationals were imposed in 18 Latin American countries at the urging of the U.S. In Peru, Japanese newspapers and schools were closed; licenses for hunting, fishing, and firearms possession revoked; and bank accounts frozen. Gatherings of three or more Japanese Peruvians were forbidden, resulting in arrests for illegal assembly. U.S. officials monitored aliens’ mail. Travel was restricted and telephones removed from Japanese homes. The Peruvian government expropriated farms and businesses owned by Axis nationals with little or no compensation. It also nullified rural property contracts, forcing immigrant tenant farmers to leave or labor for a daily wage.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, Guatemala froze the assets of all Axis nationals, restricted travel and outlawed the speaking of German on the telephone. All military bases and facilities were placed at U.S. disposal. Costa Rica issued orders to intern all Japanese nationals.

“All the moneys were frozen and we were only allowed to withdraw money for our daily living. If one exhausted his merchandise, the investigating officer no longer came.”

— Kishiro Hayashi, Japanese internee from Peru recalling restrictions imposed on his business by Peruvian authorities.

“Enemy Alien” & Individual Exclusion

In late January and early February of 1942, the U.S. Department of Justice agreed to a War Department plan that would allow the Army to establish “prohibited zones” from which all “enemy aliens” would be banned. These areas, mostly on the West Coast, included harbors, defense plants, military installations, and power plants. Those who lived in such zones would have to move or face arrest. Those who worked in the zones lost their jobs. They could not visit their own sons in uniform at military facilities. The thousands of German, Italian, and Japanese aliens ordered to leave coastal and military zones were never individually charged with any wrongdoing. They were simply part of a group – immigrants whose country of origin had become the enemy.

The Army’s Western Defense Command had pushed for the wholesale forced removal of the Japanese population, and then proposed the forced removal of all the remaining Italian and German “enemy aliens” as well, including those on the East Coast. When the Justice Department resisted, the Army proposed an individual exclusion program to order selected naturalized citizens of German and Italian ancestry to leave the military zones, which included most of the coastal states.

Members of the Buccellato and Cardinalli families who were ordered to leave the prohibited zones could only find housing in migrant worker bungalows in Oakley, California, 1942. Courtesy of Leo Buccellato.

“My father’s interrogation by the FBI began in March 1941 – well before the nation was at war – and continued until September 1942. At no time was he allowed to know the names of his accusers or the nature of their accusations. The immediate results of the board’s decision…were my father’s automatic expulsion from California, the loss of his professional position, and most importantly, his forced separation from his wife, his 7-year-old daughter, and his 5-year-old son.”

— Colonel Angelo de Guttadauro, recalling the ordeal of his father, a naturalized citizen of Italian descent, under the individual exclusion order.

The excluded individuals were given ten days to close their businesses and homes. Many in California moved to Reno, or other large cities such as Chicago, where they might find jobs. In many cases, the government advised new employers of the excludees’ circumstances, making resettlement even more difficult. Some excludees had been U.S. citizens since the turn of the century and many were in the U.S. for at least 20 years.

Restrictions on Italian aliens were lifted in October 1942, largely because of the impending Congressional elections that November, and because of the reported morale problems among military personnel due to restrictions on their parents. The support of Italian Americans was also needed for the impending U.S. invasion of Italy and for the Italian population’s own revolt against Mussolini. However, the status of Italian excludees and internees remained unchanged until late 1943 after an armistice with Italy.

Catherine Buccellato with her son, Nick. Like many others, Nick came home on leave from the U.S. Navy to find his family home empty. While he was deployed, his mother was ordered to leave the prohibited zone, which included their home in Pittsburg, California, 1942. Courtesy of Leo Buccellato.

Executive Order 9066

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, directing the Secretary of War to prescribe military areas “with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.” The order did not specify the Japanese as the people to be excluded, but everyone involved understood that Japanese aliens and citizens of Japanese ancestry were the intended target. It was meant primarily to facilitate the wholesale removal of Japanese from the West Coast, two-thirds of whom were American-born U.S. citizens.

People of Japanese ancestry were relatively few in number and geographically concentrated on the West Coast. They were also visibly distinguishable from the majority white populace, which had a long history of discrimination against Asians and resentment of their economic success. These factors, rather than any actual security threat posed by the elderly Issei immigrants and citizen Nisei, were responsible for the mass roundup and incarceration of Japanese Americans. They made an easy target and convenient scapegoat.

“I saw my Japanese friends moved out of their homes and taken away, former classmates and childhood friends. My first reaction was one of disbelief. Shortly afterwards we Italian Americans and Germans were similarly treated because they were part of the Tripartite Alliance, the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo axis… Non-citizens, my mother among them, were forced to move from their homes to other designated areas, but not to detention centers.”

— Sergio Otino, Italian American, recalling his family’s wartime experiences in Berkeley, California.

“In the war in which we are now engaged racial affinities are not severed by migration. The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese…have become ‘Americanized’, the racial strains are undiluted.”

— General John DeWitt, memo to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, recommending removal of persons of Japanese ancestry, 2/14/42.

In the months after President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, these instructions were posted ordering all persons of Japanese ancestry — aliens and “non-aliens,” two-thirds of whom were U.S.-born citizens — to register and prepare only what they could carry for their forced removal. April 1, 1942. National Archives.

Subsequently, signs went up all along the West Coast ordering everyone of Japanese ancestry to report to “assembly” or detention centers, such as race tracks and fairgrounds. There they were held while camps were hastily built to house them in remote areas of seven western and southern states. 110,000 Japanese Americans had only a few days or weeks to dispose of their property. They took only what they could carry onto buses and trains. Many of them never recovered their possessions and had to start over with nothing after release from the camps.

Thousands of Italian and German aliens living in the prohibited zones were ordered to move elsewhere. To keep families together, many citizen spouses and children went with the alien family member, who was often the only breadwinner. Families who stayed behind were left without financial support, not knowing when the husband or father might return.

EO 9066 sparked renewed alarm among Italian and German American families, who feared they might be taken away next. Newspapers reported that the Western Defense Command was in fact pursuing its original plan to remove all “enemy aliens” of German and Italian descent from enlarged military areas beyond California and the West Coast, including coastal areas in the Eastern and Southern Defense Commands. Eventually, the plan was stopped at the highest levels of government. The logistics and politics of evacuating over one million Italian and German aliens nationwide would have been overwhelming.

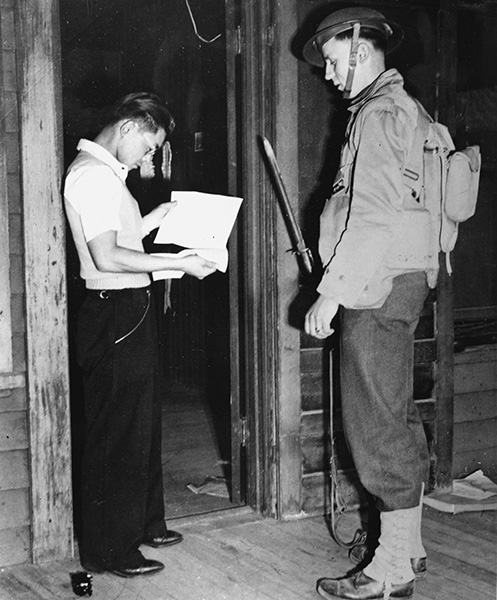

Japanese American receiving government orders to leave Terminal Island, California, within 48 hours, February 25, 1942. National Archives.