Interned

German, Japanese, and Italian alien residents from the United States and Latin America were detained or interned at more than 100 different locations across the country. Border Patrol agents of the Immigration and Naturalization Service operated the Department of Justice camps, located at former migrant worker and Civilian Conservation Corps camps, military bases, and prisons. Some facilities housed men only, women only, or married couples and women with children. Camp conditions varied widely, from bleak and harsh to Spartan but livable.

Acts of dissent as well as misinformation and disinformation in the mismanaged maximum-security Tule Lake Segregation Center (California) led 5,461 Nisei to renounce their U.S. citizenship. (In contrast, only 128 persons from the other War Relocation Authority camps renounced.) Renunciants from Tule Lake were treated as “enemy aliens” and nearly 2,000 were sent to Department of Justice camps in Santa Fe (New Mexico), Fort Lincoln (North Dakota), and Crystal City (Texas).

Japanese “enemy aliens” arriving at Fort Missoula internment camp in Montana, where Italians and Germans were also imprisoned, ca. 1941. Courtesy of Lawrence DiStasi.

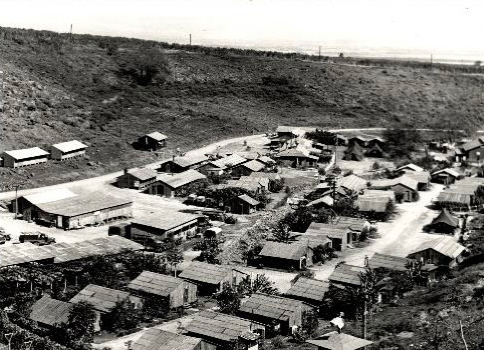

Temporary barracks at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota, during the winter of 1942-43. Courtesy of John Christgau.

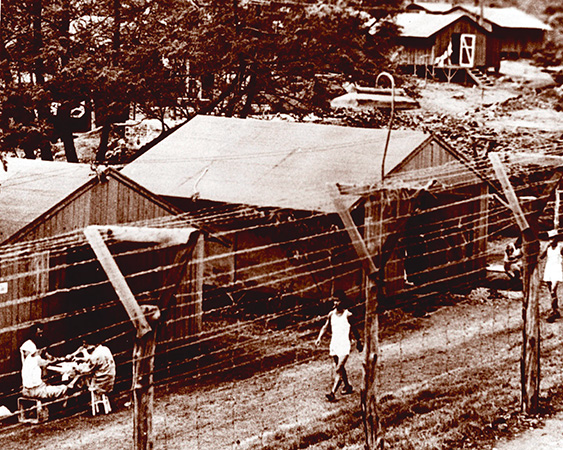

U.S. Army facility at Hono’uli’uli, Oahu, Hawai’i. University of Hawai’i, H. Lodge Photo Collection: Japanese Internment Relocation Files, Folder 273.

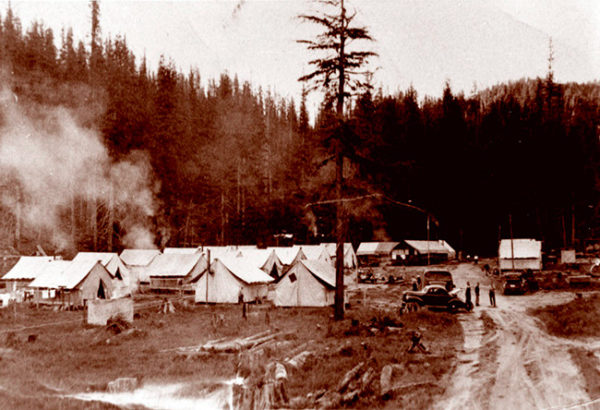

Kooskia alien internment camp in Idaho. Courtesy of Terry Abraham, Priscilla Wegars, and the U.S. Forest Service, Lochsa District, Kooskia Ranger Station.

“Without experiencing internment, no one can appreciate the intense terror of government power and the despair of hopelessness and endless time one feels. In addition, an internee must suffer humiliation, stigmatization, and suspect ‘friends’ who may have given damning ‘evidence’ to the FBI…many bear psychological scars throughout their lives.”

— Eberhard E. Fuhr, German who was interned at age 17.

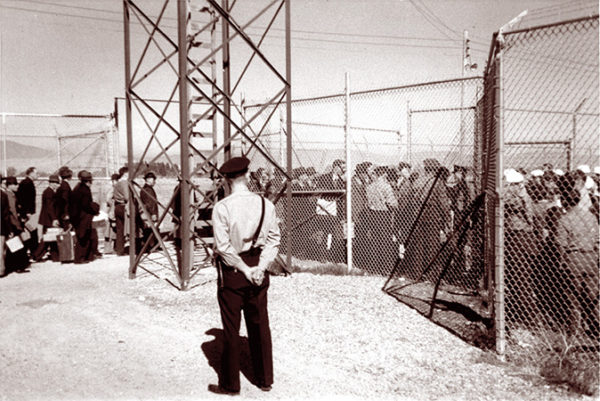

Japanese detainees arriving at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota, guarded by Border Patrol inspectors armed with submachine guns. Many were apprehended during a February 1942 mass roundup of Issei fishermen on Terminal Island in Los Angeles harbor. Courtesy of John Christgau.

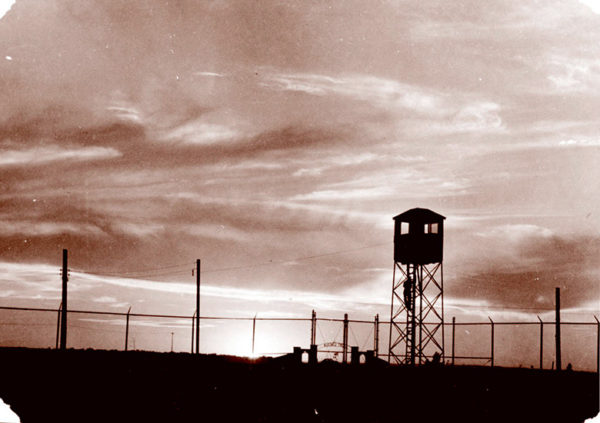

Guard tower at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota. Courtesy of John Christgau.

Initially, many of the deportees from Latin America were held on Army bases and former prisons, such as the state penitentiary at Stringtown (Oklahoma), a flea-infested, over-crowded prison where the water ran brown from the taps.

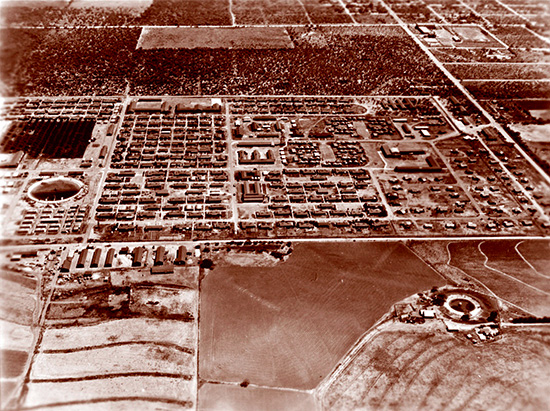

The larger of two camps designated for families with young children, Crystal City Internment Camp was the Department of Justice’s largest multi-national family camp, with a peak population of about 4,000. Hundreds of babies were born, and some internees died. One of this camp’s key functions was preparing internees for hostage exchange. Children attended schools taught in Japanese, German, or English. In the Japanese and German schools, language and culture were taught to prepare the children for life in Japan or Germany.

Aerial view of Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas. National Archives.

Often at great emotional cost, internees conducted daily life behind barbed-wire fences, klieg lights, and watch towers patrolled by armed guards with dogs. Adults strove to keep their families together through the routines of sports, school, music, arts, and community events. Thus, while many internees who were children at the time recall mostly pleasant memories of camp life, the adults and teenagers acutely felt all the realities associated with the trauma of imprisonment. Young adults missed out on education and career opportunities. Having lost the fruits of a lifetime of labor and facing an uncertain future, many adults suffered depression, listlessness, and despair. Many had grown children in the U.S. military, fighting overseas for a country that had locked up their parents.

Mail was restricted and heavily censored, with no drawings, erasures, or references to movements of internees or to the enemy nation allowed. For those in camps far from home, visitors were rare. Most of the internees were men separated from their families and loved ones. Army restrictions for internees tended to be even more severe than those imposed by the INS. Internees were housed in tents with wooden floors, four to a tent. Most were given POW uniforms to wear. They could have only two 25-minute visits per month, with all visits monitored. Any lapse into the “enemy language” was forbidden. Internees were paid as little as10 cents a day for chores they were required to perform.

Many internees spent their days appealing to the government for release. Their pleas for re-hearings were generally ignored. When the government persistently asked whether they wanted to repatriate to Germany, Japan, or Italy, some grudgingly accepted this alternative to indefinite internment. Some were threatened with the denial of family reunification unless they agreed to repatriation. Some were offered the chance to work outside the camps, such as on railroad construction. Most preferred the hard labor to the boredom of incarceration.

While the three nationalities usually got along, there was periodic inter- and intra-ethnic tension in some camps, due to political, cultural, and language differences. Some hard-core German loyalists in the camps quarreled with and intimidated those with whom they disagreed politically. Jewish internees, unaccountably placed near pro-Nazi prisoners, were harassed and sometimes beaten. Pro- and anti-fascist factions among the Italians sometimes engaged in fights. Among Japanese internees, political and intergenerational disputes were amplified by conflicted feelings of national allegiance and the prospect of family separation.

Fort Missoula alien internment camp in Montana. Four internee representatives (German, Italian, Japanese) with security officers. Goro & Nobi Asaki Collection, National Japanese American Historical Society.

Alien Internment and Detention Sites

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE (DOJ) INTERNMENT SITES

(Partial List)

Crystal City, Texas

Fort Lincoln, North Dakota

Fort Missoula, Montana

Fort Stanton, New Mexico

Kenedy, Texas

Kooskia, Idaho

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Seagoville, Texas

DETENTION SITES UNDER INS AUTHORITY

Cleveland, OH*

Cincinnati, OH*

Detroit, MI*

Denver, CO*

Detroit, MI*

East Boston, MA*

Ellis Island, NY

Forest Camp on Cougar Creek, ID

Fort Howard, MD

Gloucester City, NJ

Hartford, CT*

Home of the Good Shepherd

-Buffalo, NY

-Chicago, IL

-Cleveland, OH

-Milwaukee, WS

Omaha, NE

-Philadelphia, PA

Honolulu, HI*

Houston, TX*

Kansas City, MO*

Miami, FL, Border Patrol HQ

Nanticoke, PA*

New Orleans, LA*

Old Raton Ranch, NM

Pittsburg, PA*

Portland, OR*

Saint Louis, MO*

Saint Paul, MN*

Salt Lake City, UT*

San Antonio, TX*

San Francisco, 801 Silver Ave., CA

Seattle, WA*

Sharp Park, CA

Terminal Island, San Pedro, CA

Tuna Canyon, CA

*INS Stations

U.S. ARMY INTERNMENT SITES

(Partial List)

Balboa Detention Center, Panama

Canal Zone

Camp Blanding, FL

Camp Lordsburg, NM

Fort Bliss, TX

Fort McAlester, OK

Fort McDowell, Angel Island, CA

Fort Meade, MD

Fort Oglethorpe, GA

Fort Sam Houston, TX

Camp Florence, AZ

Camp Forrest, TN

Camp Livingston, LA

Fort Sill, OK

Hono’uli’uli, O’ahu, HI

Sand Island, O’ahu, HI

Stringtown, OK

OTHER U.S. ARMY DETENTION SITES

(Partial List)

Camp Chaffee, AZ

Camp Clark, MO

Camp Crossville, TN

Camp Florence, AZ

Camp McCoy, WI

Camp Upton, NY

Fort Richardson, AL

Fort Barrancas, FL

Fort Howard, Baltimore, MD

Fort Leonard Wood, MO

Fort Screven, GA

Griffith Park, CA

Haiku Military Camp, Maui, HI

Hilo Independent Language School, HI

Kalaheo Stockade, Kaua’i, HI

Kaua’i County Courthouse, Kaua’i, HI

Kaunakakai County Jail, Moloka’i, HI

Kelly AFB, Texas

Kilauea Military Camp, HI

Lihue Plantation, Kaua’i, HI

Maui County Jail, Maui, HI

Niagara Falls, NY

Roswell, NM

San Juan, Puerto Rico

Sullivan Lake, WA

Waiakea Prison Camp, HI

Waimea Jail, Kaua’i, HI

DEPARTMENT OF STATE DETENTION SITES

(Mostly for diplomats and consular staff as well as executives from Axis owned businesses in the U.S. and from Latin America awaiting exchange)

Bedford Springs Hotel, Bedford Springs, PA

Cascade Inn, Hot Springs, VA

Greenbrier Hotel, White Sulphur Springs, WV

Grove Park Inn, Asheville, NC

Homestead Hotel, Hot Springs, VA

Ingleside Hotel, Staunton, VA

Assembly Inn, Montreat, NC

Shenvalee Hotel, New Market, VA

The Camps

The Immigration & Naturalization Service Border Patrol operated numerous detention facilities and Department of Justice internment camps for “enemy aliens” across the country.

“Some of the people from Peru who were interned with me were separated from their families for many years. In a few cases, the broken families were never reunited. Many people are still suffering from psychological wounds caused by their internment.”

— Ginzo Murono, Japanese internee from Peru, testifying at the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians hearing in New York City, November 23, 1981.

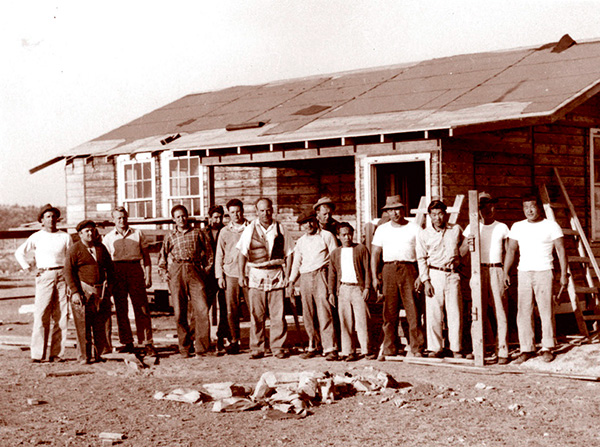

German and Japanese residents of the U.S. worked under guard to prepare the alien internment camp in Crystal City, Texas, for their families, December 1943. Courtesy of Arthur D. Jacobs.

Entrance to Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota, winter 1941-42. Courtesy of John Christgau.

Heat at the U.S. Army facility at Hono’uli’uli, Oahu, Hawai’i, forced the internees to strip to undershirts and shorts, ca. 1943. University of Hawai’i, H. Lodge Photo Collection: Japanese Internment Relocation Files, Folder 273.

Japanese community leaders at Santa Fe alien internment camp in New Mexico. Courtesy of Japanese American Research Project, University of California, Los Angeles UC2012.32.01.

Internees at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp, released to work on North Dakota railroad lines under strict guard, lived in boxcars. Courtesy of Karen Ebel.

Regulated Life

Every aspect of life for the internees was strictly regulated – eating, sleeping, bathing, work, and school. The small amount of mail they were permitted to send and receive was severely censored. They provided most of the labor involved in running the camps, directed and supervised by civilian administrators, staff, and armed guards.

“They took us to the fields [to cut sugar beets] by truck with more guards and machine guns than prisoners. When we said we would not work under such conditions, they agreed to take us back and forth without heavy guard. We made thirty dollars a month, although we never saw the money. Instead, they issued us requisitions for purchases at clothing stores and so forth.”

— Alfredo Cipolato, Italian “enemy alien” interned at Fort Missoula alien internment camp in Montana.

Internee work crews allowed outside Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota, under guard. Here, a crew marches outside for garden work. Courtesy of John Christgau.

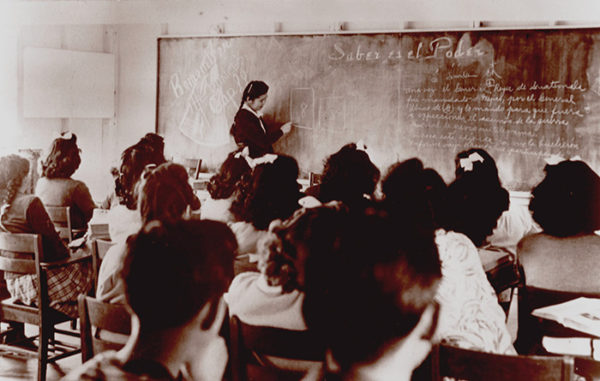

“Most of us that went to Japanese school were from Peru. We all spoke Spanish… They were preparing us to be sent to Japan. We had to learn the etiquette, language, mannerisms…not to be complete strangers.”

— Libia Maoki Yamamoto, Japanese Peruvian interned at Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas.

Japanese Peruvians in class at the Federal High School in the Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas, 1944. Kanji Nishijima Collection, National Japanese American Historical Society.

Elementary school class at Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas, ca. 1940. Courtesy of Betty Fly.

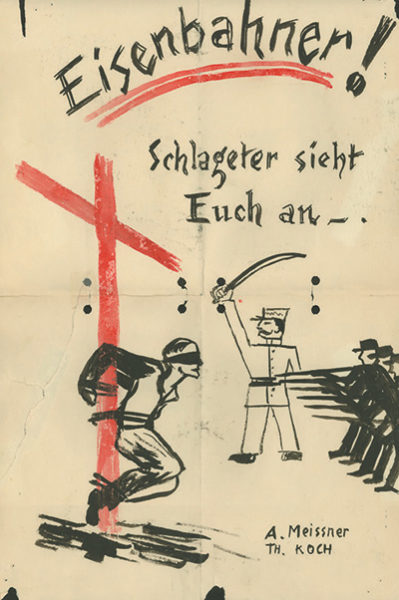

“Beware, Railroaders!” the poster reads. “The Nazis are watching you.” Put up by Nazi sympathizers at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota in 1943, the poster was meant to discourage internees from signing up for railroad work. Courtesy of John Christgau.

Interior of hutment at Camp Forrest, a U.S. Army internment camp in Tennessee for civilians and POWs, which at its peak detained over 800 “enemy aliens.”

National Archives. Courtesy of Stephen Fox.

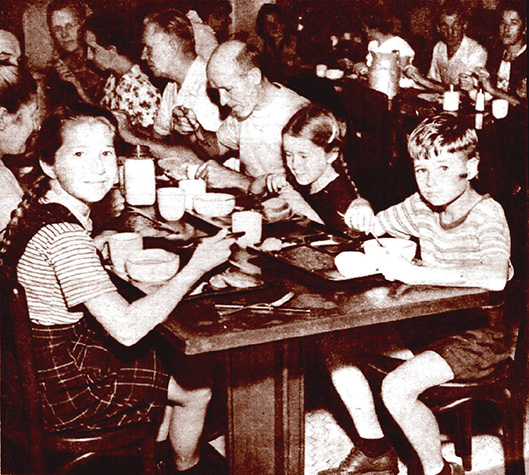

German internee family eating a meal in a dining hall at Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas. National Archives. Courtesy of Arthur D. Jacobs.

Fort Missoula alien internment camp in Montana, dining room where food was served cafeteria-style. Goro & Nobi Asaki Collection, National Japanese American Historical Society.

Cougar Creek work camp where Italian internees from Fort Missoula alien internment camp in Montana did forest work. Courtesy of John Christgau.

\

Internees of Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota, working under guard for the Northern Pacific Railroad replacing rails. Camp official selected workers, who volunteered in order to escape the demoralizing camp environment. Workers were paid a nominal amount. Fall 1943. Courtesy of Karen Ebel.

Maintaining Morale

Internees managed to organize activities to pass the time and fend off “fence sickness,” anxiety, and fear. Sports, music, gardening, artwork, and religious observances developed despite the stark conditions.

Japanese Peruvian Girl Scout Farm Project, Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas, 1944. Kanji Nishijima Collection, National Japanese American Historical Society.

A German U.S. resident playing cello, a Japanese U.S. resident on piano, and a German resident of Latin America with violin in the Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas. Courtesy of Arthur D. Jacobs.

“[My father] was…deported from San Pedro Sula, Honduras… While in Camp Kenedy…he had the opportunity to play the accordion and to teach others to play it as well.”

— Danny Eberhardt, son of a naturalized German Honduran citizen, recounting his father’s experience in a Texas alien internment camp.

German internee band at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota, that played regularly at dances held for the Border Patrol guards and their wives. Courtesy of John Christgau.

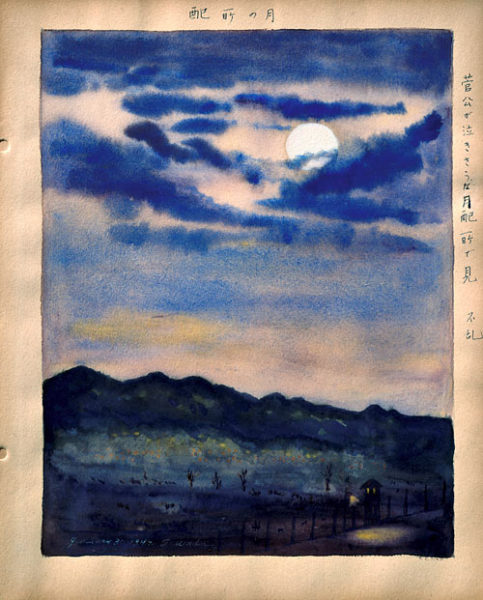

Tameichi Wada. Lonesome Moon. January 30, 1944. Painted while interned at Santa Fe alien internment camp in New Mexico. Haiku poem by Furan written on the border reads, “Kankō ga naki sōna tsuki haisho de mi. Kankō also would cry under the moon I saw in exile.” Courtesy of Brian Minami, Minami Pictures.

Interior of barrack at Fort. Missoula alien internment camp in Montana. Goro & Nobi Asaki Collection, National Japanese American Historical Society.

Casino created by German internees at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota, spring 1944. Japanese internees, although kept in a separate compound from Germans, enjoyed spending time here. Courtesy of John Christgau.

“I made friends with many Austrians, who were nearly all ski instructors…built a ski “slope” by hand, no power tools at all. We put up this roughly forty-foot structure that you climbed and skied down… I did my first downhill skiing on that damn thing.”

— Heinz John, German internee held at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota.

German soccer team at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in North Dakota, summer 1941. Internees organized barracks athletic teams and engaged in league competitions. Courtesy of John Christgau.

German internees built this ski slide at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp for winter practice on the otherwise flat North Dakota prairie. Courtesy of John Christgau.