Arresting U.S. Residents

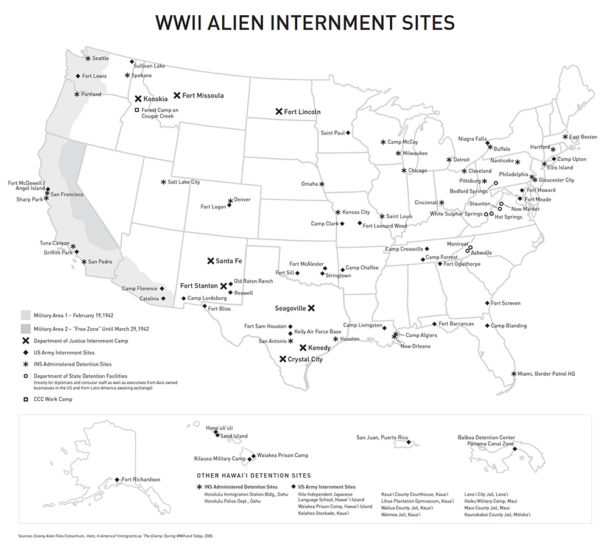

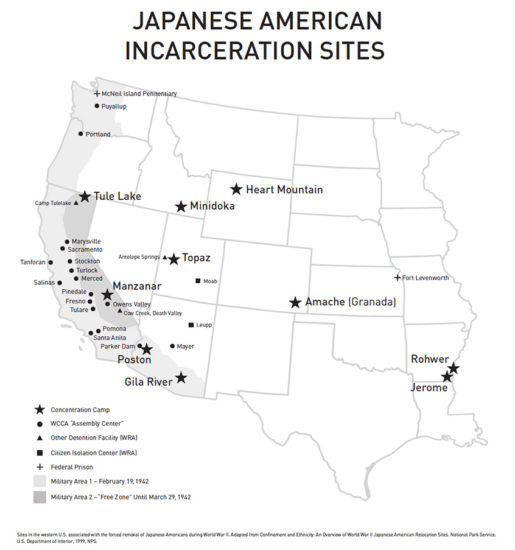

The apprehension and internment of U.S. resident “enemy aliens” began the evening of the attack on Pearl Harbor, with more than 1,000 taken into custody by December 8, 1941. By February of 1942, approximately 3,849 persons had been interned: 2,192 Japanese, 1,393 Germans, and 264 Italians. By war’s end, the number of those detained had reached at least 31,275 – 16,849 Japanese; 10,905 Germans; 3,278 Italians; and some 200 Hungarians, Bulgarians, and Romanians. Though not all were formally interned, they were held for periods ranging from a few days to several years. Among those arrested were some U.S. citizens, but neither they nor the “enemy aliens” ever learned of any charges against them.

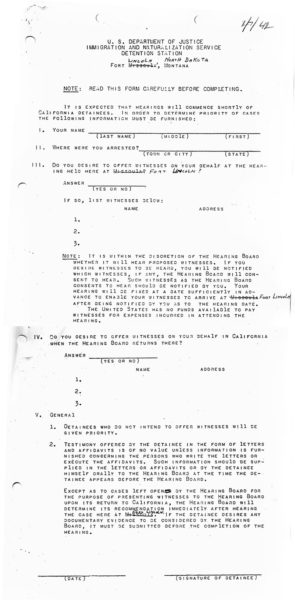

The procedure for detaining and interning “enemy aliens” in the United States had been worked out between the Justice and War Departments in the months before the war. Suspect individuals would be taken into custody by the FBI and other government agencies based on their custodial detention lists, and turned over to the INS for detention. Ellis Island in New York served as a detention facility longer than any other site, from 1941 to 1949.

Detainees’ families often did not know where they were for weeks. Sometimes both parents were taken and the children were left to fend for themselves until relatives or the local government took custody. Many women struggled to support their families and, having lost everything, sought refuge in family internment camps.

Each detainee would be given a hearing to determine if he or she would be formally interned. As the War Department had insisted, the males slated for internment would then be turned over to the custody of the Army, for internment at facilities being hastily prepared, often at Army bases throughout the nation. Female internees would be sent to INS facilities, primarily the one at Seagoville (Texas).

“They questioned me for a couple of hours: ‘If your German cousin came up the Ohio River in a U-boat and asked you for shelter, what would you tell him?’ Being a smart-ass fifteen-year-old, I told him the Ohio was probably too shallow for a U-boat. Besides, a German cousin wouldn’t speak English, and I don’t speak enough German.”

— Eberhard Fuhr, German resident recalling his hearing in March 1943 before the Civilian Alien Hearing Board, which ordered him interned.

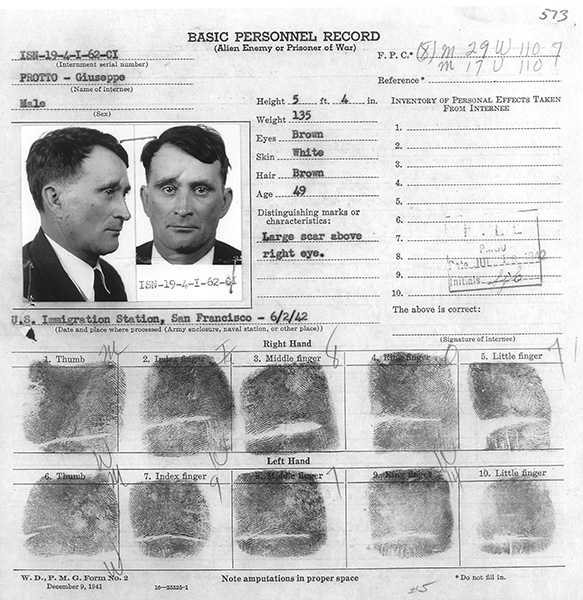

Giuseppe Protto’s Basic Personnel Record, one of the forms generated by the Provost Marshal General’s office for all “enemy alien” internees. June 2, 1941. National Archives.

On the East Coast, internees of Italian or German descent picked up in New York City would be taken to Ellis Island for detention and a cursory hearing. If they failed to “prove their innocence” to the three-person civilian hearing board, the detainee would most often be sent to the internment facility at Fort Meade (Maryland). Most internees were then shifted from camp to camp, for unknown reasons. Italian internees at Fort Meade were sent after some months to a similar facility at Fort McAlester (Oklahoma). Many internees in the West took different routes, moving from an INS facility to an army base on Angel Island (California), then to Fort Sam Houston (Texas), from there to Camp Forrest (Tennessee), and then to Fort McAlester, and Fort Missoula (Montana). Japanese arrested in Southern California were usually sent to INS facilities at San Pedro or Tuna Canyon before being transferred to other INS camps at Fort Missoula, Fort Lincoln (North Dakota), or Santa Fe (New Mexico). Many were then interned at Army camps at Lordsburg (New Mexico), Fort Sill (Oklahoma), Camp Livingston (Louisiana), and Fort Bliss (Texas).

The very first West Coast German and Italian internees, detained in early December 1941, were sent to the INS internment camps at Fort Missoula and Fort Lincoln before they had hearings. This was due to the demand by the Western Defense Command that these “dangerous” individuals be removed from the Ninth Corps area immediately. After hearings, they too were transferred to army-run camps in Texas and Oklahoma, or paroled. By the end of 1943, 1,037 Japanese aliens living in Hawai’i had been taken into custody and sent to U.S. mainland camps.

By May of 1943, with captured Axis military personnel coming to the United States for imprisonment, the Army asked to be relieved of its civilian internees. Thus, all internees were returned to the custody of the INS, with Italians returning to Fort Missoula and most Germans sent to Fort Lincoln. Japanese internees were kept mainly at Fort Lincoln, Fort Missoula, and Santa Fe until many went to War Relocation Authority camps to join their families.

Internees who had applied to be reunited with their families remained at family camps at Crystal City and Seagoville, both in Texas.

Internees could request re-hearings, which were granted infrequently. In late 1943, after Italy had surrendered and joined the Allies, many Italian internees were released on parole. An unknown number remained at Fort Missoula until April 1944, when they were either paroled or sent to Ellis Island (New York) for possible deportation to Italy at the end of the war. They joined large numbers of German internees who were also scheduled for deportation at war’s end.

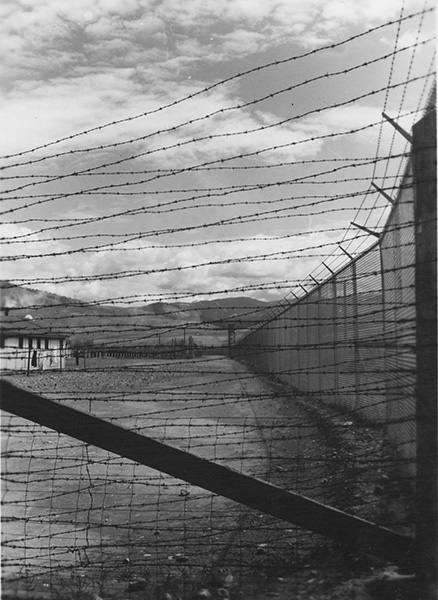

Fort Missoula alien internment camp in Montana. Goro and Nobi Asaki Collection, National Japanese American Historical Society.

Creating “Illegal Aliens”

The Japanese, Germans, and Italians from Latin America who were sent to the United States endured a grueling journey aboard transport ships in the custody of armed U.S. guards. Men and women were separated. Women stayed in cabins with their children, while men and teenage boys were kept below deck, often for days at a time, using open buckets as latrines.

The ships docked at ports in New Orleans, Los Angeles, or San Francisco. There, Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) officers asked passengers to produce a passport and visa. However, the State Department had ordered its Latin American consuls not to issue visas to these prisoners. Army and Navy personnel had confiscated all their identity documents and passports while en route to the U.S.

“When I was 22 years old, I was abducted from Bolivia, where I had lived for nearly three years… No explanation was given… We were herded into DC3 airplanes marked with American symbols. The windows of the plane were boarded up, and we were not told where we were being taken. We were guarded by armed U.S. military personnel.”

— Sadaharu Sakamoto, Japanese Bolivian internee and named plaintiff in Mochizuki v. USA lawsuit, recalling his abduction and transport to Panama.

“Mother had given birth to her fifth child… As a result of the trauma, mother was not able to nurse this baby, and so she stuffed many of the bags with Carnation milk. Aboard the ship, however, all foodstuffs were thrown overboard by the Marine guards. No matter how she gestured and pleaded, the armed guards would not understand that she wanted milk or water for her child. When she offered her breast to the crying baby, only blood came.”

— Elsa Higashide Kudo, Japanese Peruvian internee.

The prisoners listened bewildered as INS officials told them they were entering the United States illegally. These “illegal aliens” were then forced to strip and were sprayed with insecticide. They were loaded onto trains, often under cover of night, with blinds drawn over the windows. The new internees from Latin America were sent to some 15 INS facilities scattered throughout the United States.

Among the Latin American internees were 81 Jews, most from Panama and British Honduras. Those who were refugees from Nazi Germany or seemed in any way “suspicious” were taken to Balboa Detention Center in the Panama Canal Zone for U.S. Army interrogation. Afterward, they were sent to Seagoville (Texas), Stringtown (Oklahoma), Camp Algiers (Louisiana), Camp Blanding (Florida), and Fort Oglethorpe (Georgia). The latter two were run by the Army for Axis POWs and Nazi sympathizers – dangerous places for the Jewish internees.

The declaration of war also created another category of “illegal aliens” – the nearly 3,000 German and Italian merchant seamen whose ships happened to be docked in U.S. or Latin American ports. Their ships impounded, these sailors were sent to internment at Fort Lincoln (North Dakota) and Fort Missoula (Montana).

“We did not want to come to this land. We were forcibly brought here by the United States Government on a United States military transport and put in a barbed wire enclosed camp… So how can it be said that we were ‘illegal aliens’?”

— Art Shibayama, Japanese Peruvian internee and a petitioner for redress in Shibayama, et al. v. USA, Case 12/545, at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Civil Wrongs & Human Rights

Each nation has its own civil laws governing the rights and protections of citizens and residents. There are also international laws that protect individuals, especially in times of conflict. Aliens in the United States and those brought from Latin America – many classified as “enemy aliens” and others who were citizens of neutral nations – lost their protections and were subjected to civil and human rights violations during World War II.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States began the abduction and internment of Latin American citizens and residents in the name of its own national security. This violated international laws prohibiting forced deportation, forced labor, indefinite detention, hostage-taking, and placement of civilians in war zones.

“The forcible detention of Japanese in Peru, arising out of a wartime collaboration among the governments of Peru, the United States, and the American republics, was clearly a violation of human rights and was not justified by any plausible threat to the security of the Western Hemisphere.”

— John Emmerson, Third Secretary to the U.S. Embassy to Peru, 1942-43.

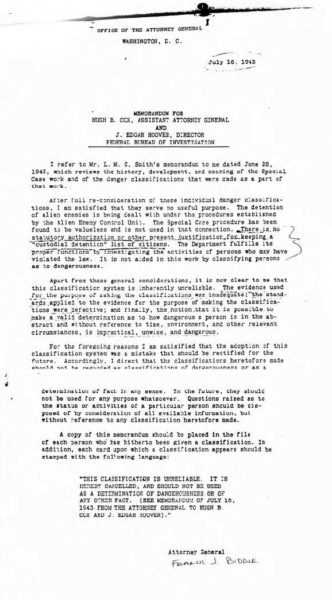

This July 1943 memo from the office of the U.S. Attorney General to Assistant Attorney General Hugh B. Cox and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover invalidates the “Custodial Detention Index” of “potentially dangerous persons.” The reasons for listing such people are “inadequate” and “defective.” Courtesy of John Christgau.

By late 1942, U.S. officials knew that there was no evidence to support the Latin American deportation program. Early in 1943, the Justice Department sent Raymond L. Ickes to Latin America to observe the detention and deportation process. Based on his report, Attorney General Biddle and Edward Ennis, the director of the Alien Enemy Control Unit, began holding cursory hearings for incarcerated individuals, leading to a decrease in deportations. Nonetheless, the program continued until 1945.

“I think it is undesirable for the written record to show that the initiative came from [the United States]… I fear that in the post-war period, unfriendly leaders in the other republics may use incidents such as this to demonstrate…the United States was really interfering in the internal affairs of the other republics. I see no reason why we should give them written evidence…”

— John Moors Cabot memo to Philip W. Bonsal (Chief of the American Republics desk, DOS), 11/15/43.

The International Red Cross and representatives from neutral nations visited the U.S. camps to observe conditions and treatment of prisoners. Nevertheless, civil and human rights violations occurred both in the U.S. and in Latin America, especially Cuba and Panama. Detainees in the Panama Canal Zone were jailed in unsanitary camps and subjected to forced labor, such as clearing brush and building barracks in midday heat. U.S. soldiers plundered their Red Cross packages. Panama residents had their homes looted, their money confiscated.

In the United States, some interned aliens reported beatings by guards, handcuff restraints, threats with unsheathed bayonets, solitary confinement, forced labor, and untreated illness. In a few cases, internees died by gunfire, and several committed suicide.

“We were put to work clearing the jungle around the camp. One extra hot, humid day we had to dig a pit. I had a terrible thought that it was to be my grave… As we carried the buckets of human waste to the pit, we retched and were sickened by the indescribable stench. The guards…laughed and jeered at us… The older men were so tired that they could not run fast enough to please the guards, so they were poked and shoved by the guards with bayonets.”

— Arthur Shinei Yakabi, Japanese Peruvian internee recalling his detention in Panama.

“Enemy aliens” residing in the United States were often apprehended on the basis of hearsay and rumor, or association with allegedly dangerous organizations. They were held without legal representation. During brief hearings to determine their guilt or innocence, they were not told the charges against them and were again denied legal representation and the opportunity to confront witnesses. None were formally charged with a crime. Even character witnesses had to be pre-approved by the civilian hearing board. The Attorney General’s office would often order internment, overriding a hearing board’s more lenient recommendation.

In some cases, naturalized citizens born in Axis nations were stripped of their U.S. citizenship. This “denaturalization” process set into motion their eventual internment, deportation, or “repatriation.” U.S citizens who were spouses or children of aliens were also subjected to internment, hostage exchange, or post-war deportation.