Breaking the Silence

During WWII, the U.S. government assured the public that it was protecting national security by publicizing arrests of “enemy aliens.” But in the 1980s, during three coram nobis cases, it was exposed that the U.S. government lied to the U.S. Supreme Court about the military necessity for the incarceration of 120,000 U.S. citizens and permanent residents of Japanese ancestry. It is also now known that government officials concealed specific details of the Justice Department camps and the hostage exchange program from the American public. Guards at the alien internment camps have reported being required to sign statements agreeing not to reveal information about the camps. The Japanese, German, and Italian internees were also warned not to talk. Some have reported signing oaths of silence with which they complied all their lives, fearing government retaliation.

Kiku Hori Funabiki displays her father Sojiro Hori’s “enemy alien” jacket, while testifying about his internment at the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians hearing in San Francisco, California, August 12, 1981. Copyright. Isao Isago Tanaka Photo. Tanaka Photo. Courtesy of Isao Isago Tanaka Family.

“My father, who died in 1990, always believed that actually the US took us in, when the Peruvians kicked us out. And he was very grateful for the US generosity. A sense of justice and fairness is one critical American ideal that my father admired. But I wonder now what my father would think if he knew what we know now, the reason why we were taken from Peru.”

— Kazuo Matsubayashi, Japanese Peruvian internee.

Mathias and Johanna Eiserloh and their American-born children were interned at Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas and reluctantly “repatriated” to Germany. The family now shares their wartime experiences on websites. Photo, ca. 1943-1944, from Lothar Eiserloh. Courtesy of Karen Ebel.

After WWII ended, those interned often kept these stories hidden. Because the U.S. government labeled them as disloyal, many felt shame and fear long after the war and didn’t discuss their experiences, even with their own families. Many internees were reluctant to talk to researchers or allow their real names to be used in books and articles.

Inspired by movements of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s for civil rights, peace, national liberation, and social change, the Japanese American community across several generations led research, education, and political organizing efforts related to their wartime experiences. The Japanese American redress movement pursued litigation and legislative strategies culminating in the passage of the landmark Civil Liberties Act of 1988 for reparations.

“My father and mother did not complain even once…I guess they hid it in their hearts…. So we must tell it to the next generation.”

— Carmen Higa Mochizuki, Japanese Peruvian internee and named plaintiff in the Mochizuki v. USA redress lawsuit.

The Freedom of Information Act of 1966 enabled historians and political activists, as well as ordinary citizens, to obtain classified government documents related to the WWII internment of “enemy aliens.”

Japanese, German, and Italian communities in the United States and Latin America have taken charge of preserving their own stories through oral history interviews, exhibits, publications, and films to document their WWII experiences. Not only are they researching, documenting, and analyzing history; they are making history.

“[We] remaining internees, much as we would like to keep these experiences locked away…we owe it to others to publicize the whole story so that what we suffered never happens again.”

— Eberhard E Fuhr, German immigrant who grew up in Cincinnati Ohio and was interned at age 17.

Some books about the WWII “enemy alien” experience. For more resources, see the Enemy Alien Files online store.

Violation of Rights

The legality of the forced removal of civilians from other countries and their internment during wartime has never been addressed by the U.S. Supreme Court. However, many legal scholars agree that U.S. citizens and aliens experienced violations of rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights in the U.S. Constitution, including:

1st Amendment Freedom of religion, of speech and of the press and to peaceably assemble and to petition the government for redress of grievances

4th Amendment Protection against unreasonable search and seizure

5th Amendment Right to due process, equal protection of the law

6th Amendment Right to counsel and trial by jury, including the right to confront witnesses, be informed of the charges, be tried by an impartial jury

8th Amendment Protection against cruel and unusual punishment

13th Amendment Prohibition against slavery, involuntary servitude

14th Amendment Right to due process, equal protection of the law by state and local governments

International Law

By the time of WWII, it was well-established that the following actions of the United States government were violations of international law.

- Forced transfer of civilian populations from neutral to belligerent countries

- Rendering people stateless

- Forced repatriation

- Forced labor

- Indefinite internment of civilians

- Hostage-taking

Many of these principles had been articulated in Article 23, General Order No. 100 of the U.S. Army (1863) or “Lieber’s Code” and the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. At the end of WWII, they were confirmed and codified by Article 6 of the Charter of London, which established the basis for the Charter of the International Military Tribunal – Nuremburg Charter and Military Charter for the Far East – Tokyo Charter, and Control Council Law 10.

In Search of Justice

The first public call for Japanese American redress came in 1970. A bill proposed in 1979 would have given $15,000 plus $15 for each day in camp to all interned Japanese, Aleuts, Germans, Italians, and Latin Americans. This bill died in subcommittee.

Responding to pressure from the growing movement for Japanese American redress, Congress set up the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) in 1981. The Commission was charged with reviewing the impact of Executive Order 9066 and the military directives on U.S. citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry to recommend appropriate remedies for those affected. Hearings were conducted in nine cities across the country, with testimony from more than 750 witnesses and the examination of over 10,000 documents.

Seven former internees of Japanese ancestry from Peru and the son of an Italian excludee were allowed to testify at the CWRIC hearings. Despite many requests, no German Americans were allowed to offer written or oral testimony. While the CWRIC produced a lengthy report centering on the treatment of persons of Japanese ancestry in the U.S. and Hawai’i as well as Alaskan Aleuts and Pribilof Islanders, it gave little attention to persons of German and Italian ancestry. The effect of this omission has been a continuing lack of public knowledge and marginalization of the experiences of these communities.

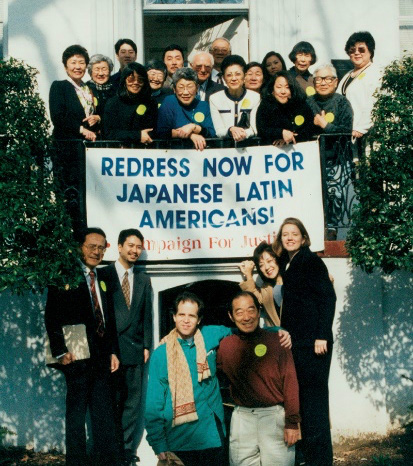

A delegation of redress supporters for Japanese Latin American and Japanese American internees. Washington, D.C., 1997. Courtesy of Campaign for Justice: Redress NOW for Japanese Latin Americans!

In 1988, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act (CLA), granting redress to U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents of Japanese ancestry who were incarcerated during WWII. Over 82,000 received a presidential letter of apology and $20,000 each. In addition, a fund was established to promote research and education about the WWII treatment of Japanese Americans.

However, most Japanese Latin Americans (JLAs) were denied redress under the CLA. The Justice Department considered them ineligible since they were “illegal aliens” at the time of their internment. Mochizuki v. USA was filed by JLAs in 1996 seeking inclusion under the CLA. This lawsuit was settled in a controversial agreement whereby the U.S. government provided over 600 internees with a presidential apology and $5,000 each.

Having exhausted their domestic remedies through litigation and legislative efforts, in 2003, the Shibayama v. USA petition was filed on behalf of the JLAs at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), a body of the Organization of American States. In 2020, the IACHR published its ruling that the U.S. government owes meaningful “material and moral” redress to the JLAs for longstanding human rights violations. With the U.S. government’s ongoing failure to grant appropriate redress, the struggle for JLA reparations continues.

Japanese Peruvian internee Art Shibayama testifying at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Washington, D.C., March 21, 2017. Martha Nakagawa Photo. Courtesy of Martha Nakagawa.

“This was a tragic episode in my life. I carry no scars or grudges. It probably has made me more understanding and tolerant of the plight of others who I believe may be unjustly accused. But I will never forget what we endured.…Now, realizing that grave errors were committed, it is time for Italian Americans living in the U.S., citizens or not, to have a public apology delivered to them for the unlawful actions taken at that time.”

— Sergio Otino, reflecting on the forced removal of his mother from their family home in the prohibited zone in Berkeley, California. He felt the repercussions of her “enemy alien” status when he served in the U.S. Navy and was denied a promotion.

Italian Americans testifying in support of H.R. 2442, the “Wartime Violation of Italian American Civil Liberties Act,” at a House Judiciary Committee hearing, October 26, 1999. Courtesy of Lawrence DiStasi.

German American and Italian American groups have also turned to the courts and the legislature for acknowledgment and justice. In November 2000, the Wartime Violation of Italian American Civil Liberties Act was signed into law. It acknowledged that injustices had been committed against immigrant residents and U.S. citizens of Italian ancestry and authorized a Department of Justice investigation and report, but reparations have yet to be granted to redress those violations. In each session of Congress from 2001 through 2010, the Wartime Treatment of European Americans and Refugees Study Act, later known as the Wartime Treatment Study Act, was introduced to establish a commission to review the WWII treatment of persons of European ancestry in the U.S. and seized from Latin America by the U.S. government, and the denial of asylum to Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Europe. The bill was not passed, resulting in no acknowledgment nor reparations yet being granted to persons of German ancestry in the U.S. or to persons of German, Italian, or Jewish ancestry seized from Latin America.

German American community members testifying at a Congressional hearing on the wartime treatment of European Americans, European and Japanese Latin Americans, and Jewish refugees. Washington, D.C., March 19, 2009. December 8, 1941. Courtesy of Karen Ebel.

“The right to redress an international wrong is recognized by scholars as a fundamental principle of customary law. Recognition of this right clearly pre-dates WWII, and it has been incorporated into both treaties and international legal opinions… The failure to compensate for such violations is in itself a violation of international law.”

— Karen Parker, Esq., international human rights expert.