Can We Avoid Repeating History?

Since the end of WWII, the challenge to maintain our national security while upholding the rights of all persons in the U.S. continues. This predicament becomes more complex as we confront change. We have seen widespread dislocation due to pandemics; environmental degradation and climate change; societal insecurity due to civil strife and war; and the increasing number and influence of authoritarian regimes.

Societal instability in the U.S. is exposing chronic economic, political, and social inequities and fueling discrimination, and exploitation. Physical violence is intensifying. Often, the most vulnerable are immigrant residents, asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants. We have witnessed challenges to the U.S. Constitution and international human rights laws in recent years. Citizens are also at risk.

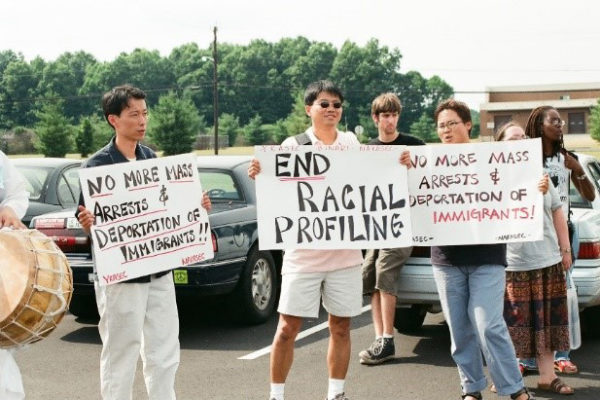

Protest rally at the Middlesex County jail in New Jersey, to demand an investigation of allegations of abuse raised by 9/11 detainees, July 2002. Irum Shiekh Photo. Courtesy of Irum Shiekh.

The FBI and other security agencies still maintain files on “potentially dangerous persons,” such as activists, members of civic and political organizations, people characterized as “terrorists” or “extremists” based on questionable evidence such as their Muslim beliefs or their appearance, as well as immigrant residents from countries considered potential threats to U.S. national security. As technology advances, the scale and scope of government surveillance and personal data collection and storage expands, often with corporate cooperation.

From the late 1940s through the ’70s – during the McCarthy era, the civil rights movement, the early years of the Cold War, and the Vietnam War – surveillance, exclusion, detention, and deportation laws were passed, and consideration was given to reopening WWII camps to imprison persons deemed dangerous or subversive in times of war or “internal security emergencies,” including war protesters.

In 1991, during the Persian Gulf War, people of Middle Eastern ancestry were subjected to intense surveillance and questioning by the FBI about their knowledge of “terrorist plans.” At that time, the government had covert plans to apprehend, intern, and deport suspected Arabs and Arab Americans. The Japanese American community, because of its historical experience, was among the first to protest this racial and nationality profiling.

Immigrant and naturalized citizen scholars and professionals, like Taiwanese American nuclear scientist Wen Ho Lee in 1999, have been monitored and scapegoated primarily because of their race or national origin. After a 2001 U.S. spy plane incident off the coast of China, several radio talk show hosts called for the internment of Chinese in the United States.

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the Bush administration launched an international military campaign, popularly known as the “War on Terror.” Without a formal declaration of war by Congress, government actions reminiscent of WWII measures against “enemy aliens” went into high gear. The WWII concept of “potential danger” was reformulated under the “100% doctrine,” which asserted that unless the FBI could say with 100 percent certainty that suspect persons were not planning an attack, the FBI should apprehend them.

“…I want our country to learn from past mistakes…. I fear we are repeating our errors, demonizing a new set of ‘enemies.’ I hear of people being kidnapped and taken to secret prisons. Targeted assassinations no longer raise eyebrows, and we debate the definition of torture…. Without open discussions, hearings, trials, right to counsel, how do we know?… We’ve been wrong before…. We have taken this road before, only to regret it later.”

— Heidi Gurcke Donald, Costa Rica-born daughter of German immigrant and U.S. citizen parents, seized with her family in Costa Rica and interned at Crystal City alien internment camp in Texas.

By 2003, more than 290,000 immigrants from predominantly Muslim nations were required to register with the Immigration and Naturalization Service, through the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS) or INS Special Registration program (which was discontinued in 2016). Some 5,000 were subjected to interviews and many experienced prolonged detention, physical or verbal abuse, closed hearings, and deportation.

The USA Patriot Act of 2001 expanded government powers to surveil (without probable cause) and investigate both citizens and non-citizens, as well as to indefinitely detain without trial immigrants and other noncitizens suspected of being “terrorists.” Property and records – even library loan records – could be searched without warrant or notification. Although the act was replaced in 2015 by the USA Freedom Act, which was allowed to expire in 2020, many of its most concerning provisions continue to be implemented by governmental agencies.

Migrants in the Donna overflow facility. Donna, TX. March 2021. Courtesy of Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas).)

After 9/11, this type of government suspicion, surveillance, and divisive rhetoric – amplified by the news media – continued to incite harassment, discrimination and violence against innocent persons based on a perception of “looking like the enemy.” Many hate crimes against Muslims and persons of Middle Eastern and South Asian descent occurred at workplaces, homes, schools, and places of worship.

Issues related to immigrant, refugee, and migrant rights persist. The Obama administration largely continued Bush administration policies of deporting undocumented migrants. Within a week of taking office, President Trump instituted a travel ban that blocked people from seven predominantly Muslim countries (including U.S. permanent residents) from entering the U.S. This led to protests at airports and numerous lawsuits.

Criminalization of asylum seekers, even children, with accusations of drug smuggling and human trafficking stigmatized migrants fleeing violence in their home countries. From the summer of 2017 to the end of 2018, the Trump administration’s immigration and deterrence policy at the U.S.-Mexico border drew international outrage. Over 5,500 children and infants were separated from their parents or guardians who were incarcerated or deported, without a government plan for family reunification. Thousands of children were separated from asylum-seeking parents. As of October 2020, 545 children remained separated because their parents could not be located.

Critical Questions Remain

Immigrants living in the U.S. who have not yet become naturalized are still vulnerable any time their country of citizenship is perceived as a threat to U.S. interests. One reason is that the Alien Enemies Act, which authorized the internment of “enemy aliens” during WWI and WWII, remains operative. It permits apprehension, forced removal, internment, and other actions against “enemy aliens” if the United States becomes involved in a war, or a foreign country threatens an invasion.

In its 2018 Trump v. Hawai’i opinion, the Supreme Court invoked Korematsu v. United States, the 1944 case justifying the exclusion (and, therefore, internment) of Japanese Americans on the basis of national security, as having been “overruled in the court of history.” In fact, however, the Court never formally overturned Korematsu, and had since applied the same logic to uphold then-President Trump’s travel ban on persons from predominantly Muslim countries. Arguably, as Supreme Court Justice Jackson holds true in his 1944 dissent, the Korematsu ruling “lies about like a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

Direct action protest against proposed U.S. immigration detention of 1,600 unaccompanied children at Fort Sill, Oklahoma (U.S. Army Internment camp) by activist group Tsuru for Solidarity with former child prisoners of U.S. concentration camps and descendants. June 22, 2019. John Ota Photo. Courtesy of John Ota.

“[N]ational security fears coupled with racism, nativism, or religious animosity and backed by the force of law generate deep and lasting damage. It is the ‘law’s stamp of approval on wartime exigencies plus racism [or religious intolerance] that transforms mistakes of the moment into enduring social injustice.’”

— Eric K. Yamamoto, et al., “Loaded Weapon” Revisited: The Trump Era Import of Justice Jackson’s Warning in Korematsu.”

Protestors at Logan International Airport in Boston, Massachusetts, January 29, 2017. Scott Eisen/Getty Images.

With the COVID-19 pandemic virus originating in China, and being characterized as such in the media, attacks on people of Asian ancestry, especially women and the elderly, have dramatically increased. Within two weeks of launching the Stop AAPI Hate tracker, in March 2020, nearly 700 reports grew to over 11,500 hate incidents by March 2022.

Many in the communities affected by the WWII treatment of “enemy aliens” agree that both public education about the past and civic action in the present are vital to preventing future mistreatment, regardless of status.

“Fears and prejudices directed against minority communities are too easy to evoke and exaggerate, often to serve the political agendas of those who promote those fears… If someone is a spy or terrorist, they should be prosecuted for their actions. But no one should ever be locked away simply because they share the same race, ethnicity, or religion as a spy or terrorist.”

— Fred Korematsu, a Japanese American civil rights activist who resisted incarceration during WWII and was the plaintiff in his landmark Japanese American incarceration lawsuit. SFgate.com opinion essay, September 16, 2004.

The critical questions remain: Can we – and how do we – balance legitimate national security concerns with the guaranteed protection of our civil liberties and human rights?

- Does the endless “War on Terror” qualify as a “war” under the Alien Enemies Act?

- With the changing nature of war, what is the relevance of the Alien Enemies Act today?

- How can we change the perception that “enemies” can be defined or identified by their race, ethnicity, religion, or country of origin?

- How do social media platforms facilitate the making of “enemies?”

- How can we prevent the deprivation of our freedoms and fundamental rights on the basis of “potential danger” rather than behavior?

- How do we hold government accountable for policies like “military necessity” or “national security” when they improperly deprive people of their civil liberties and human rights?

The answers to these questions rest in the values codified in our nation’s constitution and international law. Each generation is called to engage and to defend these principals in times of crisis. We hope this exhibit serves to bring together diverse communities to learn lessons from our histories so that truth and justice prevail.