From Immigrant to “Enemy Alien”

At dawn on December 7, 1941, the Japanese military attacked the U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawai’i. Later that day, Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Presidential Proclamation #2525, authorizing FBI agents to apprehend any Japanese alien fourteen years or older. On the following day, the President issued similar proclamations against German and Italian aliens (#2526 and #2527), and declared war on Japan. Overnight, a million law-abiding immigrants were transformed into “enemy aliens,” based solely on their country of origin. On December 11, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States.

The Justice Department’s apprehension and detention of thousands of Japanese, Germans, and Italians was authorized by the Alien Enemies Act of 1918 – U.S. Code, Title 50, Sections 21-24. Based on the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts, this law specifies that citizens (age 14 and over) of enemy nations can be “apprehended, restrained, secured and removed” in case of declared war, or actual or threatened “invasion or predatory incursion” by a foreign nation. No explicit distinction is made between resident immigrants and aliens in the U.S. on a temporary basis.

The records on the interned “dangerous enemy aliens” contain no specific evidence of subversive activities against the United States. In fact, evidence that Japanese aliens were not a threat was available but suppressed. For example, a 1941 FBI break-in at the Japanese Consulate in Los Angeles discovered memos indicating that the Japanese government considered Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans to be cultural traitors and therefore unreliable. Japan did not trust any aid or information from Japanese immigrants.

FBI agents search the Palos Verdes home of Sannosuke Ino, Los Angeles Daily News, 1942. Courtesy of Japanese American Research Project, University of California, Los Angeles. Caption research by Russell Endo.

For two months preceding Pearl Harbor, State Department representative Curtis Munson conducted an exhaustive investigation of the Japanese community on the West Coast and Hawai’i that included review of the intelligence reports from the previous ten years. The 25-page Munson Report concluded that “there is no Japanese problem.” For the most part, the report read like a tribute to the moral character and loyalty of Japanese Americans. It was quietly ignored.

“There is no Japanese problem… There will be no armed uprising of Japanese…the local Japanese are loyal to the United States.”

— Munson Report, Department of State, November 1941.

“Many of the foreign-born are not citizens, and some expect eventually to return to the land of their birth… These people as a general rule are inclined to be clannish and mix little with the communities. This is especially true of Japanese and Italians.”

— Port Director at San Francisco, California, draft memo to Director of the Naval Reserve, July 1940.

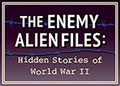

Anti-Axis propaganda poster that associated foreign language with disloyalty. Center for Military History, National Archives.)

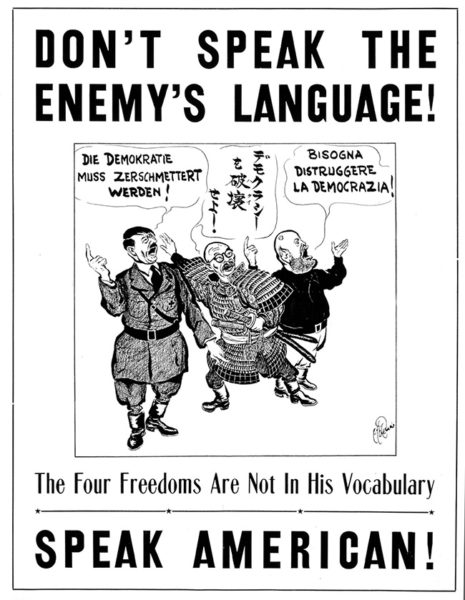

Photos of “enemy aliens” from Pittsburg, California, most of them longtime residents, were run in the local newspaper during early February 1942. Courtesy of Pittsburg Historical Society.)

FBI Round-Up

On the day Pearl Harbor was attacked, the lists that U.S. intelligence agencies had compiled for years were put into effect. By nightfall, before the U.S. had even formally declared war, FBI and other agents of the U.S. government descended upon the homes and businesses of Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants. The aliens’ homes were searched and possessions seized. Some were apprehended and detained without explanation, on grounds determined solely by the FBI. Families had no idea where their loved ones were taken, or why.

By December 10, only three days after Pearl Harbor, 3,846 Japanese, Germans, and Italians had been apprehended, charged with no crime. Local FBI agents especially targeted community and religious leaders; people with business, cultural, or political ties to their home country; editors/publishers of Japanese, German, and Italian language newspapers; and teachers at language schools.

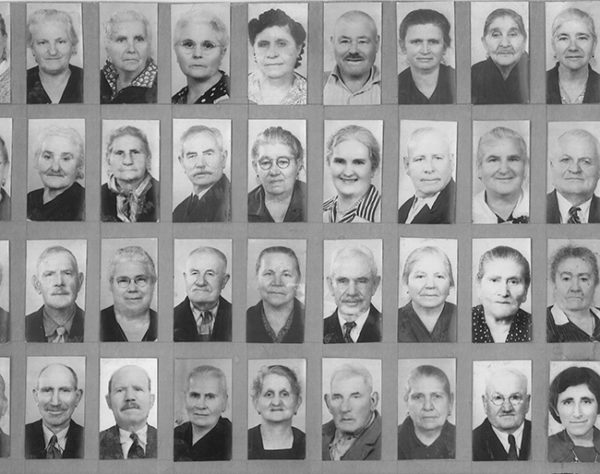

German internees from the West Coast arriving at Fort Lincoln alien internment camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, December 1941. Courtesy of John Christgau. .

“On March 23, 1943, while in class at Woodward High School, two FBI agents arrested me. I was 17. When passing through the doorways, one would precede with a drawn pistol, while the other held my left arm. When we got outdoors, I was handcuffed. I never returned to school and did not graduate two short months later. I lost not only belongings in my school locker, but my dignity.”

— Eberhard E. Fuhr, German internee who lived in Cincinnati, Ohio.

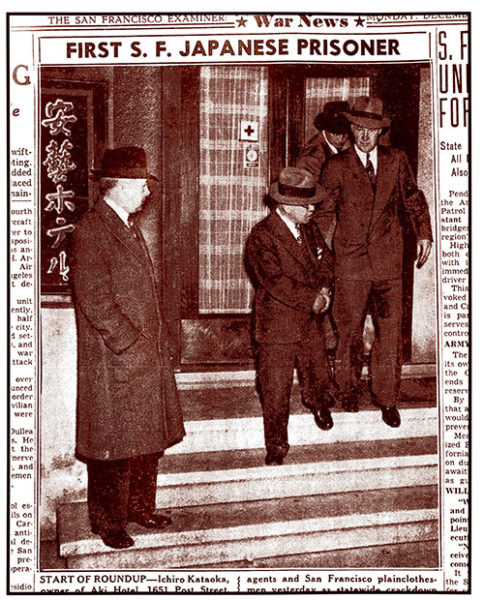

Ichiro Kataoka, owner of Aki Hotel, is one of the first aliens to be seized by the FBI, San Francisco, California. San Francisco Examiner, December 8, 1941. Courtesy of Japanese American History Archives.

In July 1943, the Department of Justice expressed serious reservations about this practice. Attorney General Francis Biddle issued a memo stating that the FBI should only investigate activities of persons who may have violated the law, rather than classifying persons as to “dangerousness.” “The notion that it is possible to make a valid determination as to how dangerous a person is in the abstract and without reference to time, environment and other relevant circumstances is impractical, unwise, and dangerous,” he wrote. In other words, the “dangerous person” label should not be used to justify wartime exclusions of citizens or aliens because it was not based on valid evidence. Only “behavior” could be evidence.

Thus, Biddle ordered the FBI to abolish its Custodial Detention Index. Instead of complying, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover simply changed the name to “Security Index” and concealed its existence from the Department of Justice. Nevertheless, the DOJ relied on FBI reports to support its program of apprehension and detention of Axis nationals in the U.S. and Latin America, which continued throughout the war, with some Germans held in U.S. detention until 1949.

Ezio Pinza, the Italian-born opera singer and star of the Metropolitan Opera, was detained by the FBI along with hundreds of other “enemy aliens” on Ellis Island. Washington Evening Star, March 13, 1943.

“I was the first one arrested in San Jose… At 11 P.M. three policemen came to the front door and two at the back… They didn’t even give me time to go to my room and put on my shoes. I was wearing slippers. They took me to prison.”

— Filippo Molinari, Italian internee who was the sales representative in San Jose, California, for an Italian community newspaper, describing being taken into custody on December 8, 1941, in a letter to a relative, 7/25/85.

The United States went outside its own borders into countries not at war, citing a threat to national security or to obtain hostages to trade for U.S. citizens stranded in war zones. Many Latin American governments went along with this for reasons of their own, although records indicate they did not believe that their Axis residents posed a serious internal or continental threat. Under a previous arrangement with the U.S., Panamanian officials apprehended persons of Japanese, German, and Italian ancestry and detained them at a U.S. military facility.

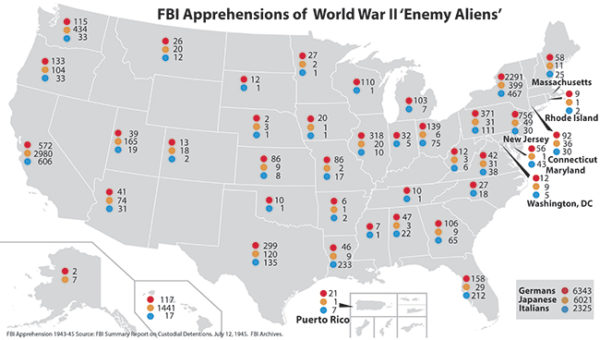

Map of FBI Apprehensions of WWII “Enemy Aliens,” 1943-45. Source: FBI Records. Mapped by National Japanese American Historical Society.

“I helplessly watched my father being led away in shackles by three Federal agents. I received so deep a wound, it has never healed. Were we so undesirable? Were we so expendable? Was I Japanese? Was I American or wasn’t I? My confused teenage mind reeled.”

— Kiku Hori Funabiki, former internee whose father, a Japanese immigrant living in San Francisco, California, was apprehended by the FBI.